Therapist In Your Pocket: Is AI The Future Of Mental Health Care?

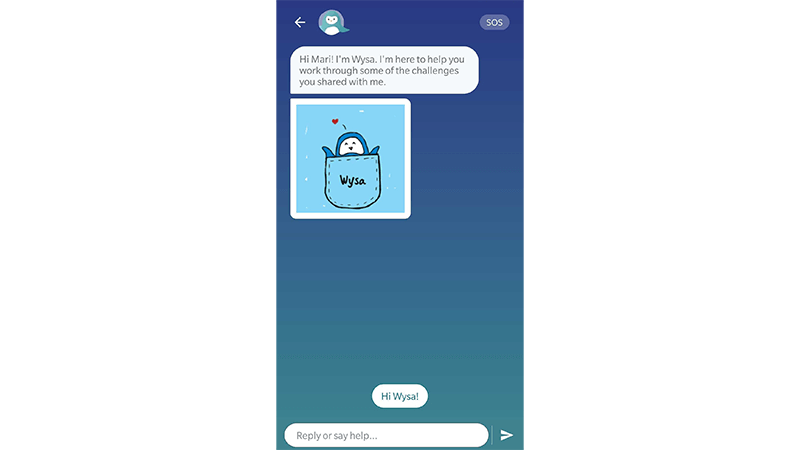

It’s Friday morning and I’m on my phone, talking to a therapist about the demands of parenting two small children while also running my business and keeping up a social life. They recommended some energy-boosting activities to help me feel less tired. So far, so normal. Except my therapist is an AI penguin called Wysa.

I’m not alone in turning to AI therapy. As mental health diagnoses soar, and support services struggle to meet demand, AI and tech-based solutions (such as RiseUp, Woebot and Youper) are being offered up as cyber saviours to this very real-life crisis. In England, mental health services received a record 4.6 million referrals in 2022 (up 22% from 2019), and in the United States, the story is sadly similar – mental health diagnoses reported in the 35-44 age group saw a significant increase from 31% in 2019 to 45% in 2023.

But is AI therapy the solution? My ‘therapist’ is a chatbot, trained to use artificial intelligence similar to Chat GPT, Siri or Alexa to engage me in text-based conversation. When I share my feelings – e.g. “I’m sad” – the chatbot trawls its database and provides what it believes is the best answer to help. It also offers mindfulness exercises, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) techniques (such as an anxiety-reducing visualisation and a free-notes journalling exercise) and ‘live text’ sessions with a qualified, human therapist.

It’s all very gamified. To answer the question ‘How are you today?’ I am instructed to use my finger to move a responsive, animated emoji and create either a smiley or sad face. It’s cute, I suppose, and very easy to use – which is one of the clear benefits of ‘speaking’ with a chatbot, instead of a counsellor or therapist. It’s also financially friendly (the basic version is free), completely accessible (no waiting lists or scheduling issues here – just open your phone whenever you like) and deeply appealing to anyone who may be nervous about, or experience stigma around, working with a real-life therapist.

Yet there are limits and concerns around outsourcing our mental health support to profit-led companies (Headspace and Ginger recently merged in a $3billion deal) and their algorithms. “People need to be as honest as possible when interacting with AI therapy interfaces,” explains chartered psychologist and author Kimberley Wilson. “The outputs [treatment suggestions] will only be as helpful as the inputs – and the algorithm.”

Even then, there’s the potential for misunderstanding – I felt I was clear while trying out another app, Elomia, but still found the chatbot’s replies confusing at times. If I were in a state of genuine distress, would this exacerbate it? Meanwhile, there have been some actual instances of chatbots getting it very wrong. Last year, a US organisation that supports people with eating disorders suspended the use of a chatbot after it advised to count calories and use callipers to measure fat. Extremely dangerous guidance and something a conscious, responsible human therapist would never dream of suggesting.

As with any AI, there’s also the potential for bias – if the data sources the chatbots are trained on are not sufficiently diverse, their ‘knowledge’ may be compromised. (It’s no secret that across AI in general, women and marginalised communities are underrepresented; a 2019 report by the National Institute Of Standards And Technology in the US found that some facial recognition algorithms had a significantly higher error rate for people with darker skin tones). Plus, there are privacy concerns – all the AI therapy apps I tried are keen to stress that the data you provide is confidential, but that doesn’t change the fact you’re giving them your (deeply personal) data.

Something I felt aware of while using the apps was the potential for serious mental health concerns to be temporarily plastered over, leading a user to believe they’re ‘getting help’ when, really, they’re just talking to a robot. A therapist relies on much more than words to assess and identify someone’s needs and provide support, and a chatbot cannot be trusted to help someone in a vulnerable situation. I tested this by telling the chatbot on Elomia that I’m having thoughts about ending my life. (I’m not.) It says it’s sorry I feel that way and encourages me to reach out to a mental health professional or trusted person. If I’d told that to a trained therapist, counsellor or coach here in the UK, they would have notified my GP (family doctor) immediately. As Wilson says: “AI is not for emergencies. If someone feels frightened about their risk to themselves or others, they should call a helpline where they can speak to a human, such as the Samaritans, or attend A&E.”

Wilson sees AI in the future of mental health care: “My prediction is a hybrid model, in which AI is used to track your everyday language and activities to alert you and the healthcare professional if there is a problem and start you on a pathway to early intervention. Or used to treat a certain type of lower-intensity condition, with human practitioners working with more complex needs.” This sounds good in theory, but if smartphones are indeed contributing to the mental health crisis, I wonder if by using these apps, we’re trying to cure an illness with the disease?

Ultimately, for now, something is better than nothing. “Globally, we have a shortage of 4 million mental health care workers,” explains Wilson. “AI has the potential to pick up a bit of this backlog – to offer access to some kind of intervention in the short term.” These apps can be brilliant wellness tools when used to support and encourage better mental health and healthy habits, but they hopefully won’t replace trained professionals any time soon.

Wilson herself isn’t concerned: “Therapy is about helping people to make sense of the absurdity of being human, so, for the moment, I am not too worried that the robots are coming for my job.”

Lily Silverton is a coach and writer and the founder of The Priorities Method