The Camera Eats First: A Glimpse Into The World Of Food Photography

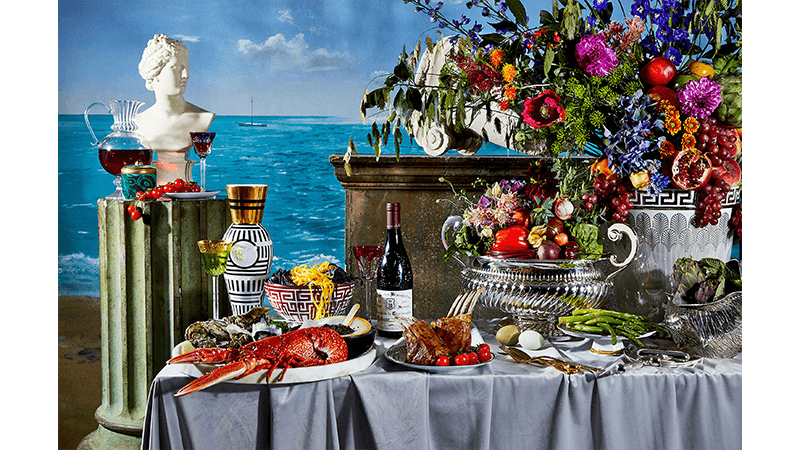

From the slow-motion shots of Carmy plating a dish in The Bear to the abundance of cookbooks with imagery so stunning they deserve a spot on a coffee table, food photography is having its moment. And while chefs and bakers once dominated the culinary social media landscape, there has been a recent influx of attention towards food photographers and their craft.

New York-based photographer Chris Simpson, who has collaborated with the likes of chef Massimo Bottura and celebrated TV cook Ina Garten, suggests that there is an emotional aspect to the increase in appetite (pardon the pun) for food-centric media. “Food is a cultural touchstone – a universal language. At a time when we’re disconnected socially and politically, people want something that feels healing in the media they’re consuming, and food is that.”

Despite common misconceptions about culinary photography, prop food and drink are typically real and edible. Subsequently, there is a multitude of unique factors that photographers have to consider, such as using speciality glassware and lens filters to mitigate reflections, or the rate at which their inanimate model might melt. “Micro-adjustments can make or break the shot. It’s a matter of being quick on your feet,” says Simpson. “Food looks best when it’s first plated – the more you pick at it, the worse it’ll look.”

London-based food photographer Louise Hagger, who has shot for chefs Yotam Ottolenghi and Lara Lee, warns of some of the job’s more hazardous aspects, recalling horror stories of delinquent pets devouring props and tales of herbs with attitude. “Coriander just dies if you even look at it funny,” she jokes.

Despite culinary photography’s prevalence, Hagger notes a persistent lack of awareness about the industry. “I had a conversation with a documentary photographer who was shocked that I earn a living just doing food photography – he couldn’t imagine that there would be enough work, which I thought was funny,” she continues. “But go into a supermarket: the shelves are full of brands who all need imagery.” Not to mention the sheer abundance of cookbooks, magazines and restaurants.

For NYC-based videographer and photographer Jenna Gang, the job has one aim: “You want people to feel hungry – to look at your photo and say, ‘My mouth is watering.’ And that’s the challenge, because not all food naturally looks delicious.”

Food and drink imagery is a collaborative effort that relies on the talent of food stylists, chefs and prop designers to help make the product look as appetising as possible for documentation. Gang recalls a photoshoot she did for McDonald’s when the company sent 300 burger buns, and the food stylist meticulously went through and selected the most appealing ones to include as props.

“People fail to realise the weeks, sometimes months, that go into a project. There’s a lot of time and thought put into what we do. We don’t just grab a sandwich from the fridge and take a picture,” Gang says. It’s a notable contrast to the ubiquitous photo dumps of half-drunk cocktails and bread-basket tablescapes that permeate our Instagram feeds. As Gang highlights, the level of creativity and skill that a professional food photographer brings to their work is precisely what sets them apart.

Jamison Kent is a freelance arts and culture writer based in London