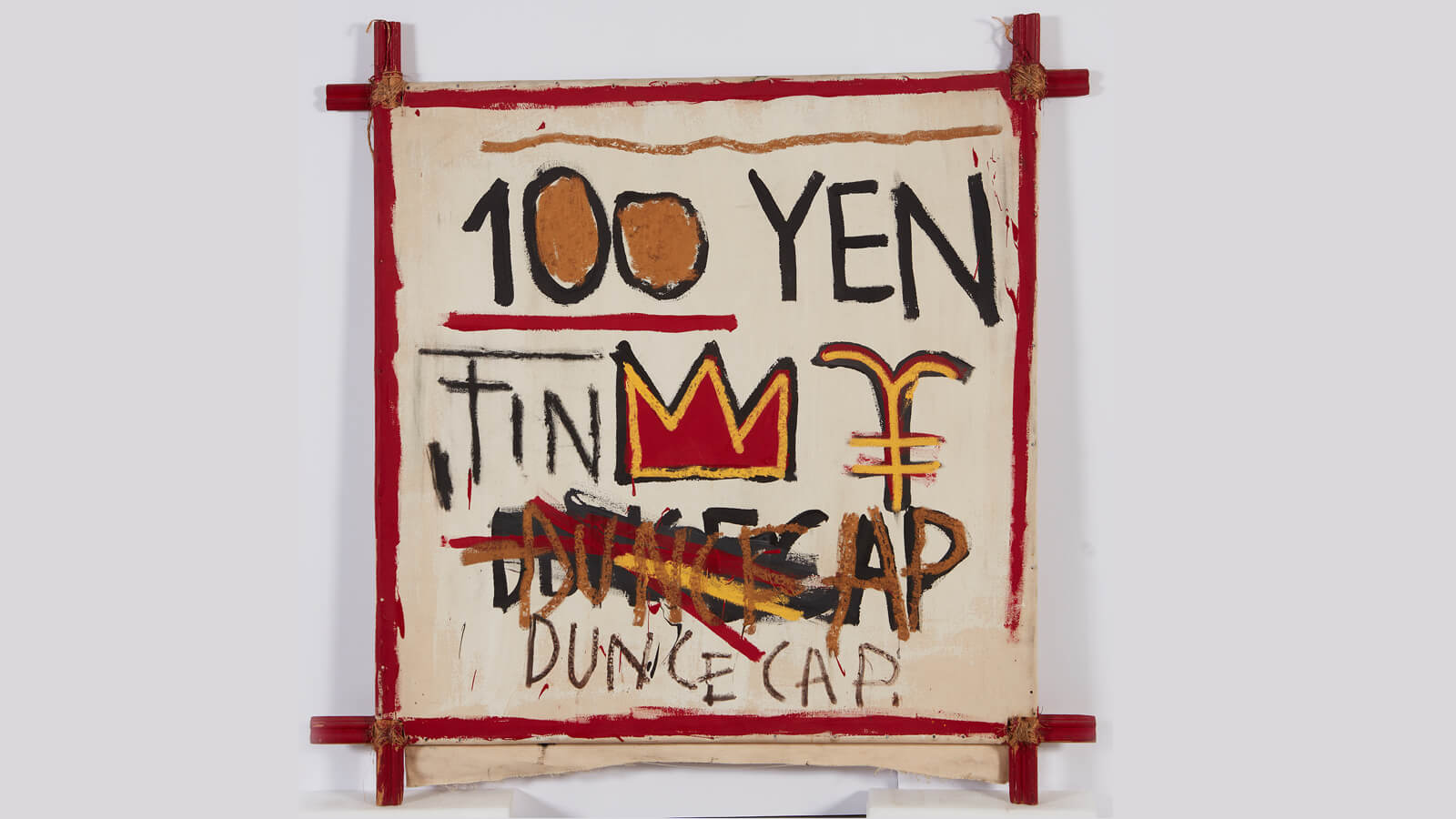

The Genius Of Jean-Michel Basquiat: “He Was The Last Of Himself. He Cannot Be Recreated”

To coincide with the new exhibition Jean-Michel Basquiat: King Pleasure in New York, the late artist’s close friend and muse, creative director and stylist Karen Binns, looks back on their time together

In the early ’80s, I used to attend poetry readings in the East Village in New York. It was the beginning of the graffiti art, creative and hip-hop scene so marked a great moment. It was here that I’d see Jean. But I didn’t know who he was. Soon afterwards I went to the famous Roxy club and an artist friend of mine introduced me to Jean and I suddenly realised, ‘That was the guy from the poetry meetings!’ We didn’t hit it off; he was joking around and slapped me on the arse so I threw a drink in his face. A week later, I saw him at another club and he said, “Please can I buy you a drink?” It was his way of trying to apologise.

Later, he said, “I’m having an art opening tomorrow and I have my little sister with me, but I don’t want her to be exposed to the press. Could you meet me at the gallery beforehand and take her to get ice cream?” I was a little suspicious, but in the end I agreed. It was only when I got to the gallery that I realised exactly who he was. He was smoking a big joint and wore a white-pyjama look with flip-flops. He sold every piece that night and we went back to his studio to celebrate. He said, “I really like you because you didn’t like me when we first met, and probably still don’t, but I feel I can trust you.” And so our friendship began.

We got on well because everyone around him was always trying to get something from him, but I never asked him for anything – not a painting, nothing. I just felt and knew he was brilliant. We hung out a lot, watching movies, at clubs, at events and at local restaurants.

We weren’t ever lovers; Jean was like a brother to me. We connected because we were constantly aware of what it was like being Black in New York in the ’80s: being misunderstood, being looked over and being treated like sh*t. We would have a lot of conversations about this. And about art. He once dragged in three old doors bolted together that he found on the street, painted on them and it became one of his most famous pieces. Andy Warhol was a great friend of Jean. One night I had a handkerchief that I spilled red wine on and both Andy and Jean signed it. I lost it. That would be worth so much now…

Eventually, drugs – especially in the ’80s – destroyed so many creatives. I was in London when I was told he’d died. I get choked up even now talking about it. He had his whole life ahead of him. The devastation was impossible to bear.

Still, he left me and the world with so much. He was also very conscious of where he came from; he lived right across from a homeless shelter and used to say, “I live here because I’ll always remember that I too was once homeless.”

‘Legacy’ was one of his main words to me. He always said if we don’t leave legacies, what we have will not continue. That’s why a lot of his paintings drew from the past; he was really into ancient writings and Egyptian art.

He was the last of himself. He cannot be recreated. He cannot be copied. He cannot be blueprinted. He was the first to defy the fact that he could be one of the world’s greatest artists. This Haitian boy, once homeless and later absorbed by drugs, actually had all the keys to the kingdom.

Karen Binns is a creative director and stylist, and was a close friend of the late artist Jean-Michel Basquiat