Desire Is A Spectrum, Not A Scale: What We’re Getting Wrong About Sex Drives

When I first moved in with my boyfriend, I expected that we’d have sex all the time. Call it the influence of books, films or sitcoms, but I thought living together involved a huge amount of time spent having sex in all positions in every room of the house.

I’m forgiving myself because I was 20 years old and not as far into my career – which involves researching sexuality – as I am now. But my assumptions pointed to an incredibly unrealistic view of sex, especially the idea of ‘drives’ and how they intersect with gender.

I grew up believing that men were obsessed with sex and that women would have to spend a lot of time batting it away. So, when we moved in together and that wasn’t the case, I worried. Maybe I was unattractive. Maybe I was ‘nagging’ him too much – this was, after all, something I overheard middle-aged men complaining about all the time. The most upsetting of questions I asked myself, though, was whether there was something wrong with one of us. Maybe I had a libido so high, or in his case so low, that we were unwell.

I confided in friends and, surprisingly, they shared similar conflicts. They too wanted sex more than their partners, and also worried that there was something immoral or even pathological about their desires. Like me, they found themselves googling ‘what’s a normal sex drive?’

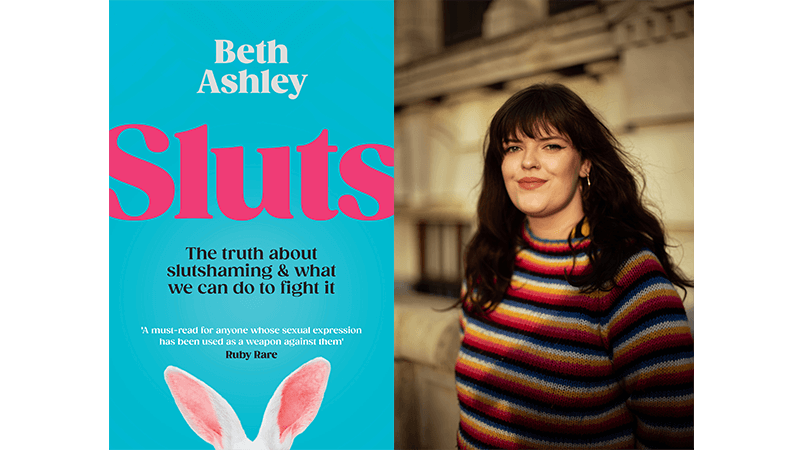

Fortunately, studying sexuality for my job gave me an insight I might otherwise have never been exposed to. When it came to researching and writing my own book, Sluts: The Truth About Slutshaming & What We Can Do To Fight It, I learned key information that changed my view of sex forever:

Sex drives are not actually real.

According to research from leading sex psychologist Dr Emily Nagoski, laid out in her book Come As You Are, as well as the sexual response cycle developed by researchers in 2000, the idea of the sex drive is not scientifically backed. ‘Drive’ is a word used to describe the motivational systems that help us navigate life-or-death situations, such as the drives to find food, warmth or shelter. But sex is not necessary for survival (no matter what some people might tell you).

Instead, our sexual desire exists on a moving spectrum. One singular person is unlikely to have a ‘high sex drive’ their entire life, or even for an entire day. Instead, it moves up and down constantly, for everyone. Though I describe myself as having a high libido, I know it’s more accurate to say it comes in waves. There have been times where I’ve had sex multiple times in one day. There have been others where I’ve not thought about sex for weeks. Most people are the same way – up and down.

On that spectrum, there are two distinct types of desire that most of us will relate to. Spontaneous desire – which many people associate with men – is a sudden feeling of horniness that doesn’t require much intimacy or stimulation before engaging in sexual activity. Because this type of desire is, well, spontaneous, those who experience it often get labelled as having a ‘high sex drive’.

On the other hand, responsive desire builds through things like physical touch, intimacy and affection, and is often associated with women. For many reasons, including poor sex education and unrealistic media portrayals, many of us expect sex to always be spontaneous, so people who predominantly experience responsive desire instead are often misread as having a ‘low sex drive’.

Of course, all genders can experience both types of desire and should never be judged for subverting from these expectations in the bedroom. Once I learned more about the realities of desire, I realised I’d been punishing myself through a form of internalised slut shaming, which the myth of ‘sex drives’ interweaves with. Men are celebrated for behaving ‘promiscuously’ and expected to have high libidos, while women are punished for the same sexual behaviour, branded as sluts – or worse. But these patriarchal standards also punish men; they can feel forced to live up to extremely high expectations of their sex lives and feel emasculated when that’s not their reality. In my case, I was berating myself for wanting sex too much.

My partner and I were struggling with sex because we believed we were the ‘wrong’ way around: I felt spontaneous desire and him, responsive. Realising that neither of us was experiencing a sex drive (certainly not a problematic one that was ‘too high’ or ‘too low’) allowed us to cater our sexual communication to our specific needs.

I found ways to touch him that promoted responsive desire, and him spontaneous for me. It enlightened us to a point where sex felt fun and joyful again, where it had felt like someone was wrong before. If that’s what this knowledge did for us, imagine if it was more known on a widespread basis?

Myths like these contribute to a longstanding pleasure gap in heterosexual bedrooms – where men orgasm almost twice as much as women. The sooner we dismantle the idea of ‘sex drives’ and think of desire as a spectrum instead of a scale, the more equality we’ll have in everyone’s bedrooms.

Beth Ashley is a freelance journalist, editor and researcher specialising in sex and relationships. She is the author of Sluts: The Truth About Slutshaming & What We Can Do To Fight It