Sex Dolls And Surgery: A New Beauty Standard

The photograph ‘Rebecca 2’ is a seemingly innocuous image: a woman sitting in a rattan chair, legs crossed, wearing beige heels. But upon a closer look, one of her ankles is awkwardly bent, the other, oddly discoloured. It turns out, the ‘woman’ is not actually real. The photograph is part of Elena Dorfman’s 2005 book Still Lovers, a series of images documenting the relationship between still sex dolls and their owners.

Almost 20 years later, things have moved on. Sex dolls are now able to talk, blink and moan, with some models even offering a full-body heating feature. As sex dolls become more human-like than ever, the number of women being pumped full of silicone – mimicking a sex doll aesthetic – has grown, too. According to a report by the American Society Of Plastic Surgeons, surgical cosmetic procedures grew by 22% from 2000 to 2020, and minimally invasive procedures by 131% in the US alone.

But why is it that, in an era when women are supposedly more liberated than ever, they still seek to achieve impossible beauty standards – perhaps best embodied by the sex robot?

A button nose, big glossy lips, impossibly large silicone breasts and butt, separated by a teeny-tiny waist: such a description can be applied to both the sex robots advertised on the websites of sex doll companies and women who have undergone extensive body modifications. One such procedure is the BBL – Brazilian Butt Lift – where fat is sucked out from one part of the body and stuffed into the buttocks. Breast augmentations involve placing silicone implants either on top of or underneath the chest muscle and with rhinoplasties the nose is cut open and sculpted. The results, however, like Dorfman’s photographs, can be eerie.

“Most people want to look proportional, but I would say maybe one in 100 wants to have the biggest butt possible, the tiniest waist possible. Nobody’s born with those proportions,” explains Dr Michael Salzhauer. Better known by his nickname Dr Miami, Salzhauer has become one of the most well-known cosmetic surgeons specialising in body augmentation, which is thanks to his skills in the operating room but also his cult social media following (2.7 million on TikTok and 1.5 million on Instagram alone).

According to a 2021 literature review, of all cosmetic surgery patients, roughly 90% are women. Among them, the use of plastic surgery to meld to societal beauty standards is widespread. Dr Miami only accepts female clients, a choice he justifies, saying it stems from the “personal gratification and satisfaction from making women feel better about their bodies… Especially women that had low self-esteem before the surgery.”

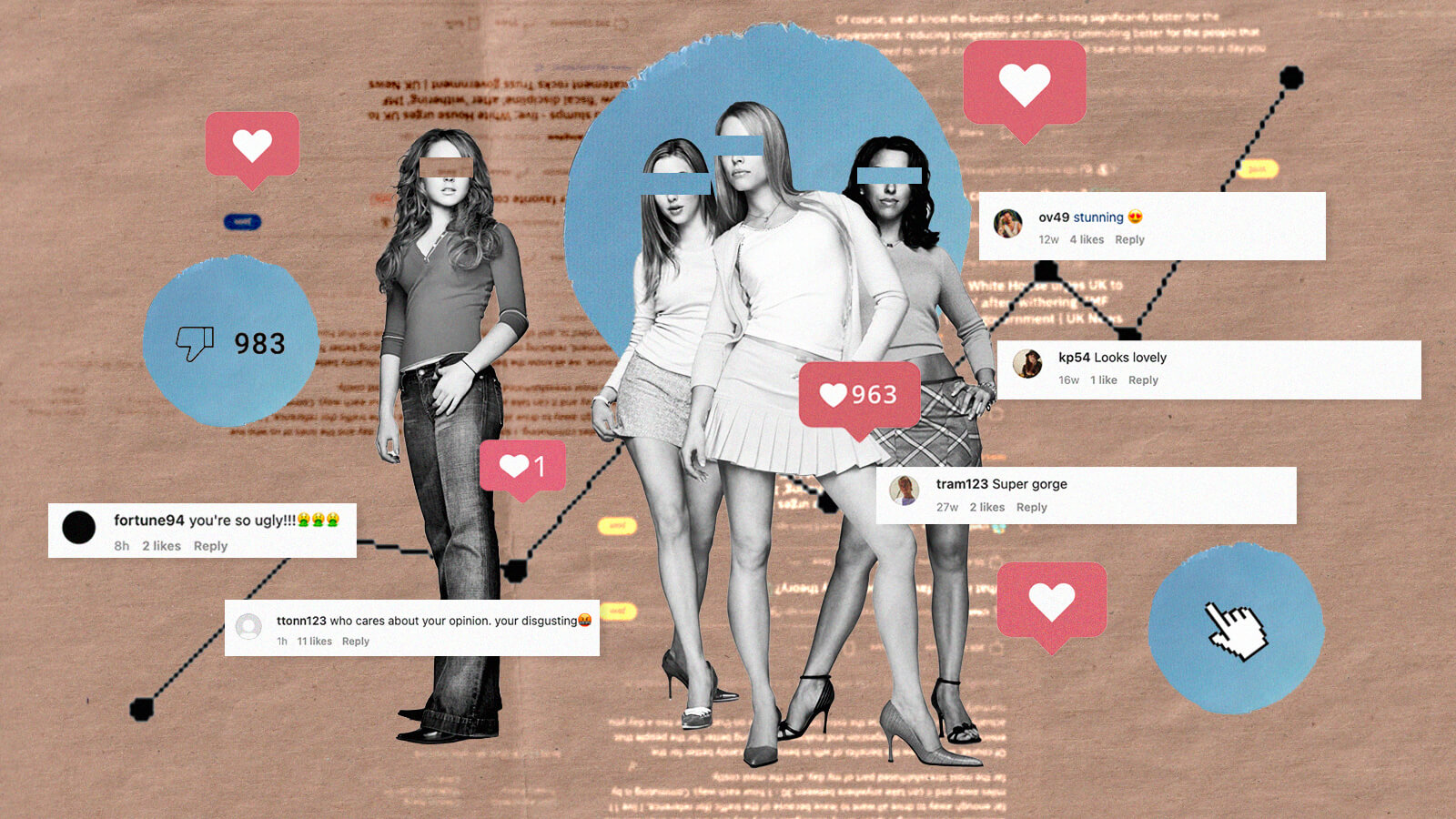

When asked about the root of intense body scrutiny that women face, there was one thing he pointed to in particular: “Social media”. And there are the stats to prove it. In a 2022 survey by the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (AAFPRS), 79% of AAFPRS plastic surgeons reported patients were searching for cosmetic procedures in order to look better for their selfies.

Studies by researchers published in various psychology journals from 2016, 2019 and 2021 analysed the correlation between social media usage and body image and also drew the conclusion that social media has also contributed to poor body image in young women. The movement for women’s bodies to resemble blow-up dolls is what many, such as Judith Regan – publisher of adult film performer Jenna Jameson’s autobiography How To Make Love Like A Porn Star – have long attributed to a societal ‘porno-isation’. As far back as 2005, Regan told CBS, “I believe that there is a porno-isation of the culture… what that means is that if you watch every single thing that’s going on out there in the popular culture, you will see females scantily clad, implanted, dressed up like hookers, porn stars, and so on and that this is very acceptable.” And, evidently, an enthusiastic audience for the content to go alongside the culture; Jameson’s book was on the New York Times’ bestseller list for more than six weeks.

But is there anything wrong with women being active agents in control of their sexuality rather than passive vessels for male pleasure?

Model Emily Ratajkowski, perhaps inadvertently, became the face of a new wave of ‘choice’ feminism. When in 2013 she starred topless in Robin Thicke’s Blurred Lines music video, it was the catalyst that Ratajkowski has admitted perfectly exemplified her politics. “I have been the poster child for choice feminism, for believing that you can call it feminism if it’s your choice. If you want to get naked or you want to dress a certain way, that can be even empowering. With Blurred Lines, I was a great testament to that… I became famous from commodifying my image and my body,” she explained in a 2021 interview in The New Yorker.

But then came her collection ofessays titled My Body in which she seemingly changed her stance. Ratajkowski explores how her self-objectification, which she previously saw as empowering, was nothing more than a chance for men to view her solely as a sexual object: “What happens when you really are just a thing to be looked at? That can be the opposite of empowering… [Modelling] is an economy – of power and of actual money – that revolves around men and their desire,” Ratajkowski told The New Statesman in 2021.

Some would argue that pornography, like modelling, sells the dream that women should not only be sexual objects, but revel in it. And, just like modelling, pornography has huge cultural capital. A 2019 study by The Shift Project found that online pornographic videos represent 27% of all online videos. Generally featuring highly produced and stylised content, the beauty ideals splashed across wildly popular mainstream pornography websites may be attributed to the sex – and race – of those behind it.

“The mainstream porn industry is basically produced, managed, directed, shot and run through the white male lens,” said Cindy Gallop, founder of adult content website MakeLoveNotPorn. The company’s mission statement says, “Real world sex is not porn. Porn is performative, produced entertainment. If porn is the Hollywood blockbuster movie, MLNP is the documentary.” Gallop’s reasoning behind her company’s ethos, she argues, is necessary as the majority of adult content is trapped under a monopoly. “The porn industry is dominated by a company called MindGeek that owns everything: Pornhub, YouPorn, RedTube, Sex.com, Men.com, Brazzers, et cetera.”

Web traffic analytics site SimilarWeb listed pornography website Pornhub as the 12th most viewed site globally for the month of June 2023, with 2.6 billion visitors (hot on the heels of XVideos.com, which nabbed the 11th spot with an extra 3 million visitors). These numbers also translate to huge revenues – according to analytics site Statista, the online adult content industry is projected to surpass $1billion dollars by the end of 2023. The power held by these male-dominated porn companies – and therefore the lack of an even, inclusive playing field – is a source of frustration for Gallop. “I have many friends – women, queer pornographers – who are brilliant, indie pornographers, and the stranglehold MindGeek has on the industry means that they don’t get the traffic, numbers, and the revenue they deserve.” Touting the importance of women-led porn films, she argues that “sex through the female lens is joyous. It’s celebratory, it’s life-affirming. It’s moving, it’s touching, it’s intimate. That is sex we do not get to see enough because, again, at the top of every industry is a closed loop of white guys talking to white guys who don’t want to let women anywhere near the power base.”

As the porn and plastic surgery industries have grown, so has the sex-doll industry. Though, interestingly, it is not limited to men. According to a 2022 study by BedBible, 9.7% of American men over 18 (approximately 9.8 million men) and 6.1% of American women (approximately 6.5 million women) have bought and own a sex doll. The same study found that despite an average year-over-year growth of 33%, sex doll sales spiked during Covid-19. Rocketing by 75%, 2020 was a record-breaking year, with $2.86billion worth of sex dolls sold.

For Dorfman, much of the allure of her original series was due to the rough-hewn look of the dolls. “You could see all their seams. You could see all the dents in their body,” she says. But, somewhat ironically, as some women have become increasingly scarred from procedures to achieve their aesthetic goals, sex dolls have become their hyper-perfected counterparts.

Rapper Cardi B told GQ in 2018 how the combination of a previous boyfriend cheating with a woman who “had a fat, big ass” and working at a strip club where women with large derrieres earned more money, drove her to resort to illegal butt injections. In an anonymous, dimly lit Queens basement, Cardi said she paid $800 for a woman with no medical experience to inject her butt with biopolymers. “It was the craziest pain ever… and it leaks for, like, five days.” Rapper Nicki Minaj also confessed – during a 2022 podcast with Joe Budden – to getting “ass shots” early in her career, saying “… this is what you’re supposed to look like in the rap culture”.

The dangers, however, are increasingly documented. In her aforementioned interview with GQ, Cardi B recalls what happened when she planned to go back for a touch-up. “By the time I was gonna go get it, the lady got locked up ’cause she supposedly killed somebody. Well, somebody died on her table.”

The pursuit of perfection in sex dolls, however, is much more straightforward. On The Doll Forum, an online messaging board where sex doll owners congregate, one member asks for tips: “I think I’m ready to design my next doll. My first doll was easy because it resembles (a lot) my ex and the love of my life.” Another thread called ‘The Life of Alita’ started in 2020 and is filled with daily posts, each documenting a day in the life of sex doll Alita in text and images. The board’s first post is filled with a long, detailed description of Alita’s backstory. (For those wondering, she’s a Paris-born dance teacher, who met her owner, “a guy with a Paris St Germain soccer jersey and pair of quad skates” at a diner in upstate New York where “they fell in love” almost instantaneously.)

For another user, the fantasy lies in a very different dynamic. “I’m drawn to the dark fantasy of ‘owning’ my sex doll, rather than pretending it’s my ‘plastic girlfriend’... it may be that I’m exploring a different dynamic, in comparison to others on this forum, but our darlings are designed and built to fulfil even our darkest fantasies.”

It is a side of technology that Gallop says “is about driving us further and further apart from each other into our own robotic, automated worlds. The side that I and other female founders operate on is about using technology to foster and improve human connection in the real world.”

Inherently, the idea of a man owning a doll that he’s customised to his sexual preferences calls concepts of male dominance, power, and patriarchal oppression to mind – topics that also factor into how women form opinions on their bodies and what makes them aesthetically attractive. In Annette Lynch’s book, Porn Chic: Exploring The Contours Of Raunch Eroticism, the author writes that society must “question whether women are free to exercise choice within an imposed patriarchal system of modesty and sexual objectification”. Such thought, defined by Lynch as ‘sexual subjectification’, is the “popular culture trend in which women and girls participate in their own objectifications, experiencing a limited degree of empowerment based on their heightened ability to attract the male gaze and desire”.

Perhaps the stark truth is that society is yet to grow beyond the male gaze, and hence gaze continues to carry cultural impact. In the same way that male sex robot owners pick the perfect face, body and voice for their dolls, women do the same when they pick a 100cc, 150cc, or 200cc implant. The only difference? While sex robots become more life-like risk free, women going under body-altering procedures have no guarantee that they’ll wake up.

Violet Goldstone is a London-based writer covering fashion and culture for titles including WWD