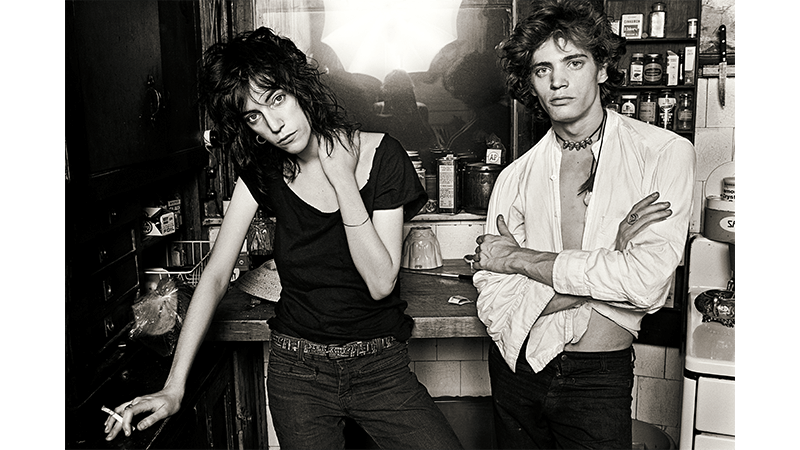

“An Alchemical Connection” – How Patti Smith Met Robert Mapplethorpe

In Just Kids – one of Dua’s previous Monthly Reads for Service95 Book Club – Patti Smith explores her beautiful and complex relationship with the artist Robert Mapplethorpe. In this excerpt, from the book Robert Mapplethorpe: The Archive, Smith describes the first weeks and months of their now-iconic partnership

When we are young we are not always adept at reading the signals of one another. A girl meets a boy and feels an alchemical connection, yet cannot guess what he is thinking. Secret wishes, shyness, or a lack of self-confidence may mask a burgeoning hope. Perhaps they will find one another, but if they don’t, she may go through life wondering – does he think of me as I think of him?

On the afternoon of July 3, 1967, I stood over a sleeping boy who awoke, then smiled at me. I have told this story many times. It is how I met Robert Mapplethorpe. I had left home with a little plaid suitcase and had nowhere to stay. I met him quite by accident, seeking shelter in the former apartment of some mutual friends; he guided me on foot to their new place. They were gone for the holidays, so I slept on their stoop on an empty Brooklyn Street. When I awoke it was Independence Day and I still had nowhere to go. However, that morning I was not thinking of my friends. I was thinking about Robert, though at the time I didn’t even know his name. On the fourth of July I took the subway back and roamed around the city, wondering if our paths would cross again.

Providence was kind and we did accidentally meet. We walked the streets of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, talking for hours. Robert was funny, gentle and a sympathetic listener. That night we went back to Brooklyn to the same flat where I had found him sleeping. Robert slid two large black portfolios from beneath his bed. We sat on the floor and he showed me his work, delicate drawings, many resulting from his visionary experiences while on LSD. One by one he laid them before me – spidery images, intertwining words, a budding twig transforming as a bird, an etching of a flower’s blooming face, disembodied insects and mandalas composed of a mystical calligraphy. His work had its roots and references, echoing artists from Redon to Henri Michaux to Pousette-Dart, yet wholly unique. As dawn approached we fell asleep together, the floor covered with his drawings.

“Having little money, we lived simply, but happily”

In the weeks to come we were inseparable. Robert searched for living quarters for us near the Pratt Institute of Art where he attended classes. We created an environment that reflected our common aesthetic, using furniture and found objects left on the Brooklyn streets on trash night. Having little money, we lived simply, but happily. We both drew, working side by side on the floor, using the same colored pencils. and brass sharpeners. I loved to watch Robert develop a drawing: he was a beautiful draftsman and easily applied this skill to form the complex yet intuitive organic shapes that formed his visual vocabulary.

That winter we found employment in a major toy emporium in the city. Robert was a window trimmer and I worked at the cash register, ringing up toys. On a coffee break I found a miniature lamb from an abandoned nativity crèche in a trash bin. The holidays were approaching and Robert suggested we make a habitat for the lamb. He made a shadow box from wood and I painted it white. I began a drawing with words as a backdrop but fell asleep. Robert stayed awake most of the night finishing it and presented it to me in the morning. I placed the lamb in his new home and we set it on the table – our sole Christmas tableau. I called it our “lamb box,” and it somehow reflected the intricate simplicity of our life together.

By spring I had a new job in a bookstore. Robert loved art books, especially large-format coffee-table books. He used to dream of having such a book of his own one day. It both delights and saddens me to see the magnificent books produced since his death emblazoned with the name MAPPLETHORPE on the cover, fulfilling his early dreams. Robert absorbed, rather than read. We had books on Surrealism, Marcel Duchamp, Tantric art, erotic art, Abstract Expressionism and Michelangelo that we perused time and again, always discovering something new. At the bookstore I scouted for books containing images of subjects that interested him and he would often cut them out for his collages. In the beginning, he gravitated toward religious imagery, evoking his traditional Catholic upbringing. His mother fostered hopes that he would enter the priesthood, but he knew, even at an early age, that he was not destined for the pulpit; he was fated to serve the muse of Michelangelo’s young David. Robert was internally ready to surmount all obstacles, and though gentle in demeanor, he possessed an unwavering belief in his own chosen vocation. He was destined to be an Artist, a calling infused with strife and revelation.

The holy Madonna, her son and the saints had dominated the world of his work, but were soon abandoned in favor of darker subjects. He switched to books on black magic, designed his own pentagrams and encouraged me to spread and redesign my Tarot deck. I gladly read for him but hid my cards, as I knew I would lose at least one face card to a work in progress. I lost two. Robert made me a Valentine using the card of the holy fool and later the card signifying evil was used upside down in a collage.

“Robert was emotionally grappling with his sexuality; our relationship had to be redefined but not our mutual work ethic”

Our makeshift gypsy caravan was eventually draped with black and deep purple satin, sewn with silver stars. Horned devil masks were spray painted red and veiled in black net. Robert moved swiftly from subject to subject. One was obliged to have an open and flexible mind to keep up with him. He was also drawn to geometric forms and devised a game-board style of arranging the space surrounding his components. An important book consulted was Tantra Art by Ajit Mookerjee. Robert studied the plates with admiration, noting the governing patterns of descending and ascending forces.

And then abruptly he turned his attention to freaks, in particular the sideshow freaks he had seen as a young boy at Coney Island. I found a large format paperback with stills from Tod Browning’s classic film Freaks and we cut them out and he mounted them on his game board like terrains. From the summer of 1967 to the spring of 1968 he worked within these diverse but relatable realms. One evening I returned from the bookstore and found him sitting on the floor cutting sailor images from a soft porn men’s magazine. I had never seen a magazine like that and was mystified by his sudden shift. Robert didn’t analyze or talk about why he did his work; any clues to the workings of his mind were laid bare within it. I didn’t attempt to interpret it, though I likened his sailor imagery to Jean Genet’s Querelle Of Brest. Robert hadn’t read Genet, so I read his books to him before he went to sleep. He was especially moved by the transformative passages in Miracle Of The Rose.

Robert was engrossed with each phase he moved through, but he was more than likely to shed them, like an impatient snake wriggling from a worn skin and sliding toward the new. He passed from religious to demonic to sideshow to sailor. But the sailor within him did not jump ship, nor was shed, but came to symbolize the blossoming of his inner nature, dominating the way he walked and dressed, the decor of our bedroom and the direction his work would be taking.

In 1969, in the midst of much personal turmoil we moved from Brooklyn to a room in the Chelsea Hotel. Robert was emotionally grappling with his sexuality; our relationship had to be redefined but not our mutual work ethic. For my birthday he made me a tie rack – a beautiful object, now in possession of the Getty Institute. He mounted a found print of the Madonna onto wood, adding a cross on a black string and my ties. Delicate pulsing areas of colored pencil appeared to radiate through her white gown, an inverted black triangle framing her benevolent gaze. As a synthesis of our past and future, the tie rack seemed to symbolize a new era for us both, the arrival of a new decade.

Robert had now fully embraced his homosexuality. He was at full sail and did not look back. His art became infused with an expanding set of references. The work and lifestyle emanating from Andy Warhol and his Factory interested him. Though usually bored in a movie theater, Federico Fellini’s Roma was a revelation and he referred to Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò, Or 120 Days Of Sodom as a masterpiece. Most of all he loved John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy and began to explore the image and lifestyle of the hustler.

The Chelsea Hotel was a charmed place to live but our room was very small, so in 1970 we acquired a raw space next to the hotel where we both could spread out, and do our work. The floor was littered with art supplies, manuscript pages, Robert’s cuttings, men’s magazines, net, chicken wire and cans of spray paint. Robert combined idiosyncratic components and transformed them into a contained work. He saved beads, claws, religious medals, black net, stars, and bits of geometry. And like Joseph Cornell’s boxes, which Robert had long emulated, his arrangement of such materials served as visual poems.

Assimilating our meager belongings, Robert created installations he would be obliged to disassemble when we needed our clothing. The cost of our workspace required sacrifice; our lack of money was daunting. But hunger didn’t bother Robert as much as not being able to acquire the things he needed to execute a vision. Often the needs of the work trumped the stomach. Men’s magazines were very expensive. Robert bought them solely to cut up for elements in a drawing. They were sealed, so he had to purchase them sight unseen. If there was nothing usable, he became frustrated for needlessly spending our money.

It occurred to me that Robert should take his own pictures of hustlers, sailors, cowboys or bodybuilders. It was a suggestion I had made earlier in Brooklyn but he had shrugged it off. Processing film and printing pictures was time-consuming, expensive and not immediate enough for his purposes. In the end, the optimum solution turned out to be Polaroid images, for he could take and use them moments later at will. The artist Sandy Daley lent him a Polaroid Land camera that suited Robert’s needs; the only drawback being the cost of pack film. When we could afford film, Robert had to work economically, making each picture count. His first pictures were of me, and then of himself. Satisfied that he had technically mastered the Polaroid, he quickly stepped out into the world newly armed.

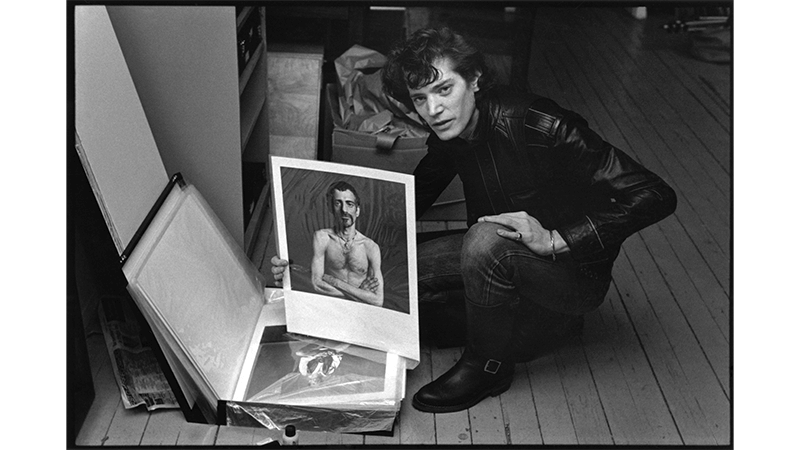

I had thought that Robert would simply take pictures to use as elements for his drawings and assemblages. But he became instantaneously consumed with photography and embarked wholeheartedly on this unanticipated course. Robert did nothing half measured. He combed secondhand stores in search of photography books and carefully studied them. Robert especially admired the great portraitists such as Nadar and August Sander. He noted that their best pictures revealed a strong chemistry between the artist and his subject.

The designer David Croland proved to be the perfect subject. He was relaxed and experienced before the camera. Slim and pale with thick dark hair, he was also an interesting reflection of Robert, allowing him to experiment and remain invisible. David introduced him to John Mckendry, the curator of photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. John allowed us to look through the flat files of the museum’s archive, and Robert was struck by the beauty and quality of the prints. Newly inspired, he was determined to move beyond the Polaroid.

David also introduced him to Sam Wagstaff, who was to become Robert’s great love and patron. Together, Robert and Sam immersed themselves in the history of photography and amassed an important and instructive collection. Both aspired to elevate the status of photography as an art form. With Sam as his patron, Robert finally had the resources with which to pursue the development of his photographic vision. For the most part, he laid his drawings aside and devoted his energies to his newly adopted medium, though his earlier preoccupation with geometric shapes was reintroduced in his intricate frame designs.

”Robert didn’t analyze or talk about why he did his work; any clues to the workings of his mind were laid bare within it“

When looking at his photographs of sculptural nudes, Robert often said that had he been born in the Renaissance he would have undoubtedly chose Carrara marble as his medium. But he was pleased with the path he had taken. For a prolific artist who revered sculpture, photography was the modern solution and the medium he chose to elevate the most complex aspects of sexuality as art.

Toward the end of his life Robert said that he had all but exhausted his classic romance with photography.

“I want to shoot animals, gorillas – then return to sculpture,” he said. “I’m going to focus on large installations.”

“Like three-dimensional drawings?” I asked.

“Maybe four,” he said, and we both laughed.

Robert didn’t live long enough to realize his plans. As he waged his battle with AIDS he shot his last pictures: self-portraits, statuary, flowers, the curve of a blood-colored poppy, an erect purple anemone, a sleeping cupid and a leering Mephistopheles. Projections of new work cruelly paraded before him. But he did not reach the cage of the gorilla. Mortal pain and immortal loss clashed as he surrendered his visions to the ether.

© Patti Smith; Robert Mapplethorpe: The Archive by Frances Terpak and Michelle Brunnick, with essays by Patti Smith and Jonathan Weinberg