“I’m After A Kind Of Writing That Feels True To How I Feel”: Author Nam Le On Poetry, Perception & The Power Of Language

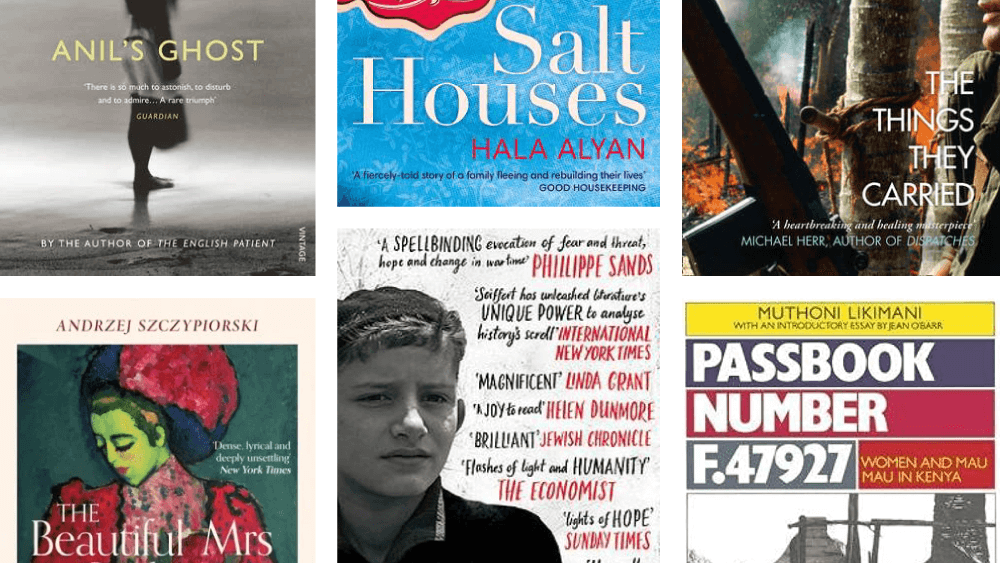

In October this year, Service95 partnered with Ubud Writers & Readers Festival in Bali to bring guests a series of events and conversations. The events featured some of the world’s most exciting authors and thinkers, sharing their expertise on topics from women’s rights in conflict to how to write a debut novel. Celebrated Vietnamese Australian author Nam Le appeared at the festival to discuss his work, including his new collection, 36 Ways To Write Vietnamese Poetry. Keshia Hannam caught up with him to discuss the necessity of truth, stepping away from assimilation and purposefully creating work that isn’t ‘easy’…

When Vietnamese Australian writer Nam Le talks about his work, he appears honest and unbothered. He declares identifying themes in his work would feel fraudulent: “That’s never been how I work. I’d only be making stuff up after the fact. Let the readers decide, I reckon!”

The lawyer-turned-author (who was admitted to the State of Victoria’s supreme court) is disarming and sharp as he calls in from Melbourne. He came to Australia as a child refugee with his parents by boat in the 1980s. As an adult, he moved to America in 2004 to hone his writing through fellowships and eventually through a master’s in creative writing. He became fiction editor at the Harvard Review and held two more fellowships before returning to Australia in 2008.

Now, Australia is home, and from there, he says his primary focus is to tell the truth. Or a truth. Truth informed by his lived experiences, and by the nature of perception. He is careful, though, to question what ‘identity work’ is. He is driven to ask: “How is this descriptor [of identity] applied, by whom, to whom, in what circumstances? What does non-identity-driven work look like?”

Le spoke at the Ubud Writers & Reader Festival about his new book, 36 Ways To Write Vietnamese Poetry. Ahead of the festival, we asked him about this captivating collection of poems, as well as some of his previously award-winning works, including The Boat.

Keshia Hannam: Your books explore the haunting and hopeful dynamic of being a refugee with honesty. What motivates you to depict these stories?

Nam Le: I’m not sure motivation is the way in for me. It’s more, as you say, a haunting – I find myself returning to certain stories and situations. People being displaced: from places, from histories, cultures, families, assumptions, expectations, identities; from their senses of themselves. Maybe it’s just that refugees are obvious exemplars for a kind of uprooting or unrooting that’s happening to all of us, in all sorts of ways.

KH: You came to Australia in a boat with your parents at only a few months old, years before the Howard Government [known for its anti-immigration policies from 1996-2007] and the Turn Back The Boats policy [introduced in 2001]. Did things get worse or better for you socially, as you got older?

NL: It was just the way things were. Was it surprising, the xenophobia? No. Was it the only thing on our minds? No.

KH: You went from lawyer to writer. Thinking about that decision now, do you feel you can serve justice more effectively on this side? Or was that never the point?

NL: This will sound highfalutin, but when it comes to writing, I think the deep allegiance is to truth more than justice. To (try – and fail – to) say how things are before trying to say how they should be. Of course, truth is more than a precursor to justice; it is, I’d venture, its essential condition. Saying something all-the-way-round true has always been bloody hard.

KH: I feel like for many folks of Colour in Australia, there is a period of your life where you have to actively step away from assimilation and reintroduce yourself. Did you have that experience?

NL: The thing about assimilation is that it goes deep, right? It changes you inwardly as well as outwardly, and the inward changes are harder to track as they’re encoded into your operating system. The same operating system you think of as being neutral, inviolable, just… there, just… you. I agree with you: a lot of us, at some stage, find ourselves trying to do that impossible thing: stepping away from ourselves to see how we became our selves.

KH: One of the first things that struck me about 36 Ways Of Writing A Vietnamese Poem was actually the design. What are you trying to say or inspire with this book?

NL: Thanks. If you’re talking about the Australian edition, ’twas I who designed it! I guess it was more what I was trying to not say: I didn’t want sepia-tinged photographs (or photographic images at all); or recognisably figurative images; oriental or exotic motifs; predictable literalisations of metaphor; conventions of beauty via landscapes, soft washes, human figures, ornaments, etc. Hence the minimalism – the brutalism. And because the book more than anything interrogates language, I figured a typographic design felt right.

KH: It feels like it wasn’t supposed to be read easy – or at least that was my experience, reading and rereading to try to guess who is the audience? And what is being criticised? What emotional place were you at when you wrote it?

NL: If ‘easy’ means knowing exactly what to think or feel, then you’re right – I’m not interested in easy. Not that I’m going for difficult. I’m after a kind of writing that feels true to how I feel, which is always in flux; which is complicated and often contradictory. The audience, and the object of criticism, isn’t fixed: it’s me, it’s you, it’s them, sometimes all at the same time. I love how you describe your experience reading this book; it approximates my experience as I was writing it!

KH: One of my favourites was 33. Euphemistic. It is an elegant call out – a way of humanising and balancing what is usually one-sided. Can you tell us about the learnings that come before a poem like that?

NL: It’s a poem about how language shapes perception, which shapes reality – all of which can be shaped by power. Shorter version: language is power, and it is shaped by power.

Keshia Hannam is a New York-based, Hong Kong-born, Australian-Indian writer, director, producer and speaker. She is editor-in-chief at the Eastern Standard Times