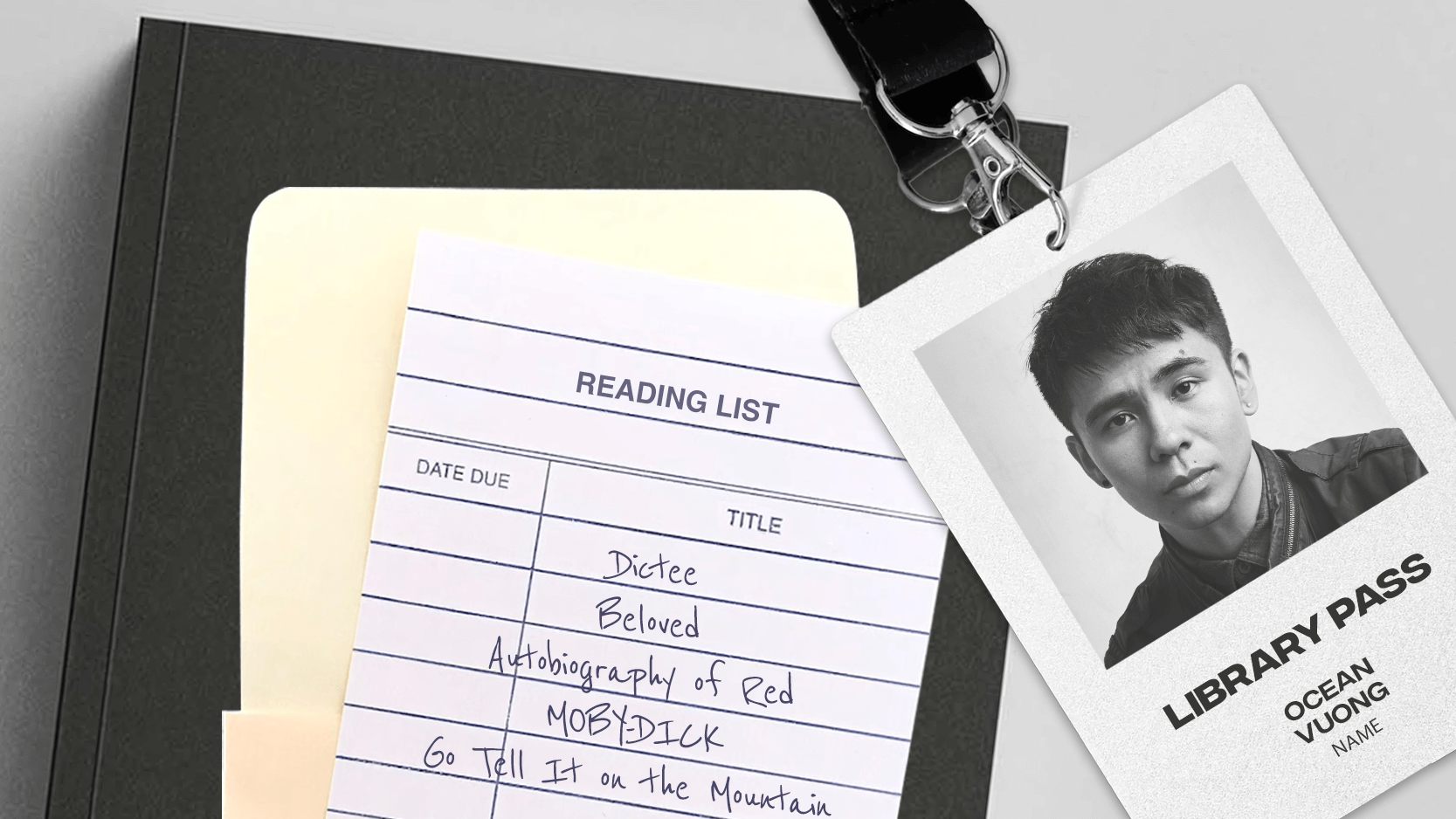

Min Jin Lee: “Pachinko Became An Organising Metaphor For My Story”

Min Jin Lee is the author of Service95 Book Club’s Monthly Read for July: Pachinko. It tells the story of Koreans in Japan during the colonial era, two wars and post-war period, through the fortunes of one family over four generations. In this exclusive essay, Lee explores the game of Pachinko as the novel’s central metaphor and reveals how the stories of real-life Korean-Japanese people changed her focus for the book entirely

At first, the working title of my novel about the Korean-Japanese people was ‘Motherland’, because I thought that’s how immigrants would view their birthplace. I wrote a draft manuscript, and when I reviewed it with the eyes of a fiction reader, I found it to be dry and self-righteous. That was rather disappointing because I’d put in so much effort and time to write it. Yet I knew it didn’t work, so I put it aside. I wrote another novel about Korean-Americans in New York [Free Food For Millionaires], which I published in 2007.

That year, my husband got a job in Tokyo. I wasn’t interested in moving there with our young son from New York. However, we needed the money, and I wanted the three of us to live together, so we went. Once I became familiar with Tokyo, I noticed that wherever I went, near almost every subway stop or major shopping area, there were Pachinko parlours.

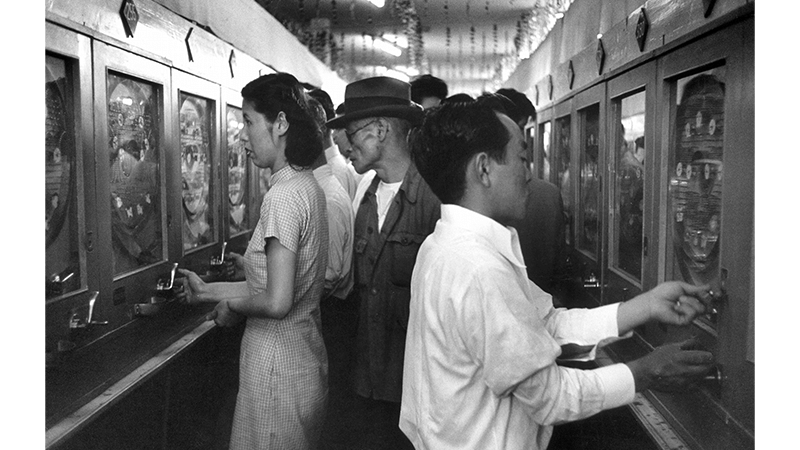

Pachinko is a kind of vertical pinball game, requiring little skill. One can play it by depressing a tiny lever, turning a dial, or by touch depending on the machine. Adults play Pachinko by feeding the machine a quantity of tiny metal balls, and depending on how the balls cascade through the vertical maze (striated with steel pins altering the ball’s course), one wins or loses. Throughout the 20th century, the game evolved from itinerant hawkers travelling to festivals or carrying the machines from village to village, to established storefronts housing dozens or even hundreds of machines. At its inception, children won candies or toys, but gradually, Pachinko became an adult gambling game.

Since gambling for cash is mostly illegal in Japan, the player would win tokens of the winnings in the form of laundry soap, cigarettes, handbags or plastic cards embedded with precious metals. To bypass the illegality, these tokens would be exchanged outside the store for cash. For much of its history, the game was associated with organised crime and tax fraud, and was seen as something bad for society. That said, since the 1990s, the industry – worth hundreds of billions of dollars – has been heavily regulated by the Japanese government, eliminating the illegalities.

The initial operators of Pachinko stalls were Japanese. But because this lucrative business was considered less legitimate and unseemly, non-Japanese people were hired when Japanese employees could not be found. Pachinko was one of the very few industries where Koreans – who suffered social, legal and professional discrimination – could work and sometimes flourish.

While living in Japan in 2007, I decided to reconsider my ‘Motherland’ manuscript. I started to interview Koreans, and I learned that nearly every person had some member of their family who had once worked in a Pachinko parlour. I visited the parlours, interviewed the owners and researched machines, of which there are countless styles and modifications. My novel isn’t about the game. No, not at all. However, the game and its culture informed my thinking of the Korean-Japanese people who have a unique and complex migration history.

Pachinko became an organising metaphor for my story. I wanted to explore the idea that life is like trying to win a game, which may have been designed to make the player lose. Koreans in Japan faced extraordinary persecution – both as colonial subjects from 1910-1945, and then as stateless subjects stripped of legal protections and left without a homeland, since it was not easy to return to a war-torn nation, divided in two.

How do immigrants, migrants, refugees and forced labourers, who have experienced colonialism, imperialism, the Pacific War (1941-45) and Korean War (1950-53), discriminatory legislation and social exclusion continue to live, raise families and pursue their goals?

It didn’t take long for me to realise why ‘Motherland’ was so wrong-minded. It was factually correct; however, it didn’t capture the randomness and destiny of individual lives in the face of structural inequity. I discarded it and started again because I discovered that the lives lived were found between the spaces of laws and historical events. I started to imagine the real lives of the Korean-Japanese with their quests, feelings, obstacles and undying wishes.

When I heard the voices of the Korean-Japanese people; when I visited where they lived, worked, and went to school; when I started to experience a bit of what they felt in this fascinating country they called home, I realised they were full of love, faith, worries, dissatisfaction, joy, humour and hope. Each day, just like all of us, they took an honest chance at an unkind world, and continued to live anyway full of heart. So, I decided to call the book Pachinko.