George The Poet On Confronting Inequality, Colonialism & The War On Blackness

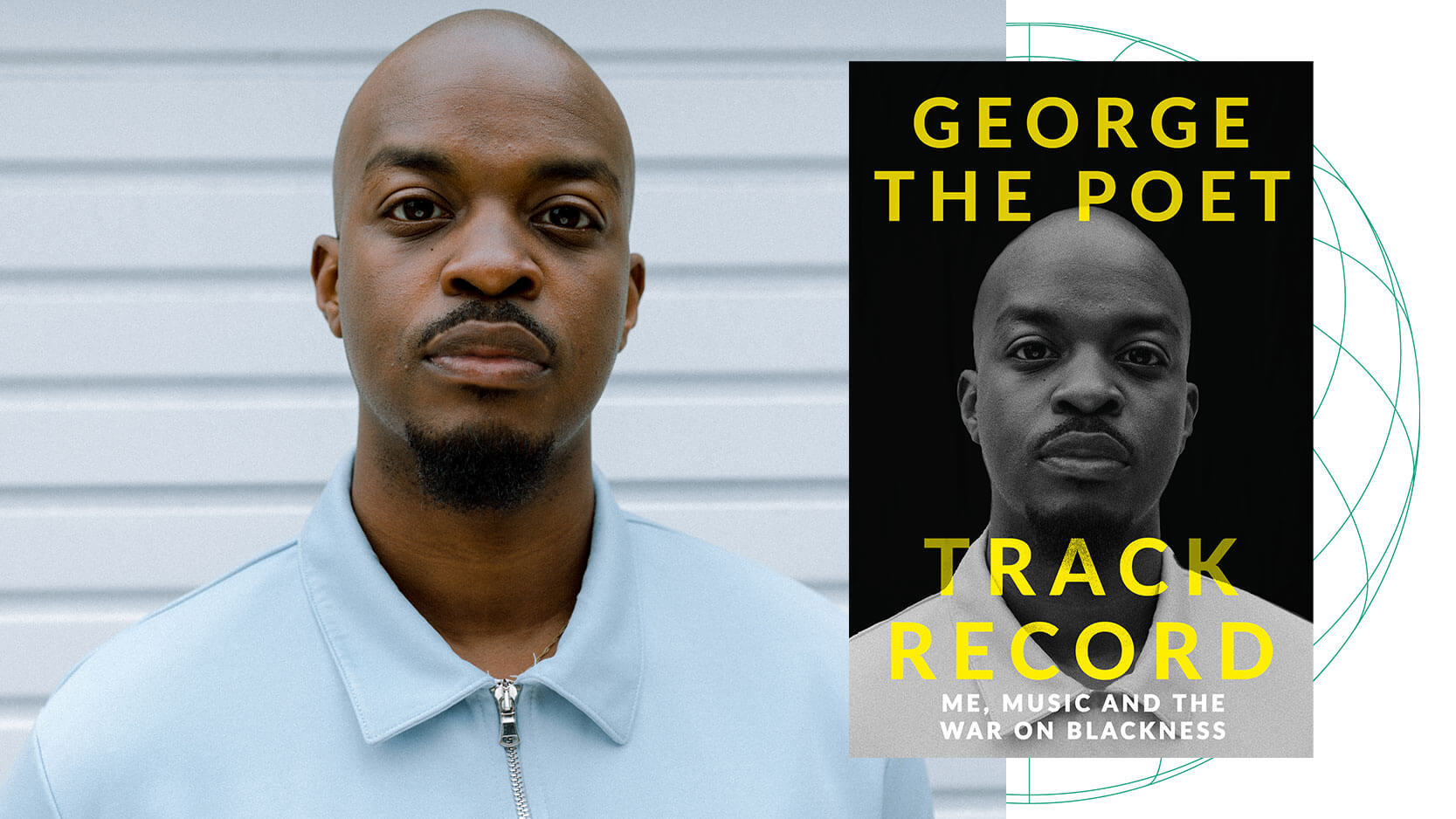

In May this year, Service95 partnered on a selection of sessions at Hay Festival, Hay-On-Wye with some of our favourite writers. Here, George The Poet – who spoke on the panel for Making Music, Making History, a conversation on the legacy and history of Black Music in the UK – talks to Olivia McCrea-Hedley about his memoir Track Record: Me, Music And The War On Blackness, which confronts discussions of race, class and structural inequality while reflecting on the story of his life so far

George the Poet catches me off guard from our first hello. The spoken word performer, rapper, podcaster and author is known for making an impact with his words, tackling topics that others are often afraid to address – from social injustice to current affairs – head-on. And yet, the man in front of me begins our conversation with a shy smile and an immediate ‘sorry’.

His team had already given a profuse apology that he’d be a few minutes late, but he still wants to be sure to deliver his own, assuring me that we can speak for as long as I need. It’s not like he was needlessly late, either – George’s one-year-old son needed him, so he was there. More than understandable.

It quickly becomes clear that this is typical George behaviour: leading with humility, self-awareness and heart. He speaks of the lyrical genius of rappers he came up in the Grime scene with, while never actually referring to the quality of his own work. When asked who his creative inspirations are, alongside listing a few high-profile names, the people he most passionately mentions are his close friends. He’s even surprised that I’ve read his book – Track Record: Me, Music And The War On Blackness – even though it’s the main reason for our conversation today.

Characteristically, despite it being a memoir, the book isn’t just about George. Instead, he uses it as a vehicle to explore the historical and political events that have shaped not only his life but also the social, political and economic state of the West, Africa and, well, the entire world.

“It was always my intention to use my career to try to explain where we come from and inspire people from circumstances like mine to break out of the box,” he explains. “But when I started writing the book, I realised that I have to talk about so much more than me. There is so much context needed that is bigger than my personal experience and it would be a mistake, a trick, to individualise everything I’ve learned when what we really need is a collective outlook.”

And so, throughout the book, which took around four years to write, George seamlessly weaves between his personal history, a history of rap music – particularly the emergence of the UK Grime scene that shaped his early identity and led to the beginnings of his career – and a wider social history. He covers everything from his upbringing on an estate in northwest London to the British Empire’s transition into the Commonwealth; the pivotal moment he wrote his first lyrics to the link between Black music and US Intelligence; landing his record deal at age 22 to the West’s 2011 invasion of Libya. Track Record is the history lesson we were never taught.

As for his personal story, George Mpanga was born to Ugandan parents in London in 1992, where he was raised with his five siblings. Unhappy with his elder brother’s schooling, his mother worked to send George to a high-performing grammar school – “a culture shock”, as he transitioned from spending most of his time in a mostly Black, working-class environment to a non-Black, middle-class grammar school. “I’d never really thought of Black people from an outside perspective before, so that was an interesting experience. It made me feel defensive and protective of our narrative,” he says.

Music played a key role in George’s early life – he recalls being in the car with his father, playing tracks from Bad Boy Records, and listening to the hip hop his older brother, Freddie, loved so much. During these formative high school years, George began rapping himself and while at university in Cambridge, he transitioned into spoken-word poetry – thinking that Grime would not translate well with his new peers. It was a pivotal shift in his creative journey.

He released his first spoken word EP, the critically acclaimed The Chicken & The Egg, in 2014, and started his Peabody award-winning podcast series Have You Heard George’s Podcast? in 2019. He’s also studying for a PhD at University College London, focusing on the value of Black art and its economic and cultural potential. Oh, and then there’s Track Record, released earlier this year.

There’s a lot to unpack – which is how the book came about. “I started off talking a little bit about me. I’d say about two years of my writing was, ‘This is my life, this is what happened,’” says George. “But then, George Floyd was killed and protests happened all over the world. And I started doing my PhD, so I went deep into research. I started reading books that you won’t come across accidentally.”

The result: Track Record is necessarily confronting, refusing to shy away from discussions of race, class, colonialism, structural inequality and the war on Blackness he so clearly highlights in the book’s title.

“The more you talk about the world, the more people you can invite into the narrative,” says George. “So if I’m saying that I feel that I had benefited from certain colonial privileges that my people had access to, that’s quite a big thing to say. But if I explain to you the nature of colonialism, and how colonised people were managed by giving some groups access, some groups a little bit of privilege, and undermining and oppressing everyone else, then you can understand a bit more where I’m coming from.”

Admittedly, it’s a lot to take in as a reader. But, through his signature lyricism, George invites readers into the conversation through pacy, absorbing prose and quotes from his own work and lyrics he loves. His writing style is unsurprising, really, considering the one thread that runs throughout every key moment in his life: music.

George approaches discussions of rap songs like a student analysing Shakespeare, dissecting the rhyming styles of different artists in the same way the rhythms of iambic pentameter are taught in schools. George explains that, for him, “rap is a form of poetry”. His artist name is George the Poet, after all.

This appreciation for music also drives the book’s historical narrative. As George details writing his first-ever lyrics in high school to Wiley’s track Eskimo, he simultaneously charts the emergence of UK Grime – the song is considered one of, if not the first, Grime instrumental ever made. As he writes about his appreciation for the rapper Tupac, George also unpicks the politics of the Black Panthers in the US: “The more I understood about Tupac’s context, his Black Panther upbringing, the politics that come with the Panthers, the dynamic with the American state, his aspirations for hip hop and just more of his catalogue, the more I understand that he was really trying to lay out a model of how we can use our music for more than just actual game,” he explains.

The book is intentionally political, down to his choices to capitalise the ‘B’ in ‘Black’ and the ‘G’ in ‘Grime’. “I think it is necessary to come out as an artist, as a Black artist, and say that these things are deeply important,” he says.

Throughout Track Record, George explores the idea that certain rappers create a certain ‘aspirational’ view of what life, and success, should be like – one that can be damaging, depending on who is consuming it, particularly young Black men whose identities these lyrics might be helping to shape.

“Hip hop is marketing,” he says. “Hip hop is advertising, in its mainstream function. Let me not dismiss the hip hop artists across the world who don’t use the music for that, but in the mainstream, hip hop is used to sell and sell and sell.

“I do believe that part of that carousel is the fact that many of us, as artists, have accepted the idea that music is primarily for commercial gain or for keeping the party going. If you can make money and you can make a vibe out of your music, I want that for you. I want that for anyone who loves the music. But we do need some kind of responsibility. We need to not trick ourselves into believing that we don’t have a responsibility, especially if you rely on the admiration of young listeners to fund your career. It’s that simple.”

It’s for this reason that George now, more than ever, makes sure to consider those who will be consuming his work during his creative process: “Whenever I write, I am trying to address the audience of unborn children who will be revisiting this material in the future to try and make sense of how they’ve got to the point that they’re at now.” It even influences his lexicon: “There’s a time for strong language; other times your language has to be strong in a different way, not just profane. It might have to be confrontational. It might have to be blunt and painfully honest; critical.”

George is someone who is well educated in the traditional sense, but in the book, he looks beyond the traditional markers of learning, referring to the education he’s had through music, lessons from his family and conversations with others. “It is hugely important for me to talk with my family, my friends, especially those back home in Uganda,” he says. “I feel like I’ve been able to use my friends and my family’s experiences as reference to what I’m experiencing over here, and that is a real form of education that is just priceless.”

Now, he’s able to share the unique mix of what he’s learned through both academic study and social experience via Track Record – not only to inform others, but to hold himself to account. “Some of the powerful, unscrupulous people in the world rely on plausible deniability. They rely on saying, ‘I didn’t know that was my role; I didn’t know that history was so biased against you and towards me,’” he explains. “That’s why I hold myself to account: I say even I benefited from certain colonial privileges of my ancestors; I say even I was a wishy washy ‘liberal’ celebrity at one point, compared to what I am now. I have learned so much that has removed me from some of the illusions that I used to hold. So I’m going to just state it publicly and invite you on this journey with me. I can never claim not to know.”

Ultimately, he hopes Track Record can change minds. “I would love for people to read my book and take from it that our story is collective more than it is individual. You’ve got to understand what the countless ancestors before us attempted – where they were successful, why they were not successful, where you fit in the equation as a result of history. Look at the world from a more collective place, rather than from the individual.”

4 Creatives Who Inspire George The Poet

- Ghetts– “Ghetts is a rapper who, when I was getting into UK rap, Grime, he was very, very much, like many of his generation – he had a lot of bravado, a lot of machismo, and over time he’s become more reflective and more political. Many of us, we don’t grow up in political education, so that’s a clear process of growth. I really appreciate that about him. I’m trying to say that publicly more because I think it privately a lot.”

- Benbrick – “My main collaboator [songwriter, composer and producer] BenBrick is endlessly creative. He’s constantly upskilling, teaching himself new things.”

- Adéṣayọ̀ Tàlàbí (@SimplySayo) – “I love SimplySayo, the poet. She’s again, very creative. She has a way of taking what’s happening in her life, sometimes a serious message, and wrapping it up in a lot of jokes. She’s a real poet.”

- Munya Chawawa– “I love [actor and comedian] Munya Chawawa. He’s another one that I just find very, very good at taking serious stuff – taking jokes, taking rhymes and throwing out ideas and concepts in very entertaining shorts. If I could achieve his level of multitasking game, I would be a much better, much more efficient machine.”

Track Record: Me, Music And The War On Blackness by George The Poet is out now

Olivia McCrea-Hedley is Copy Editor at Service95