An Exclusive Essay From George Saunders On Writing Lincoln In The Bardo

George Saunders is the author of Lincoln In The Bardo – Dua’s Monthly Read for October – following Abraham Lincoln’s 11-year-old son, Willie Lincoln, as he transcends into the afterlife. In this essay, author George Saunders explores his relationship with the novel – a contemplation of grief, death and the history of the American Civil War – and the writing process that brought the story together. Contains spoilers!

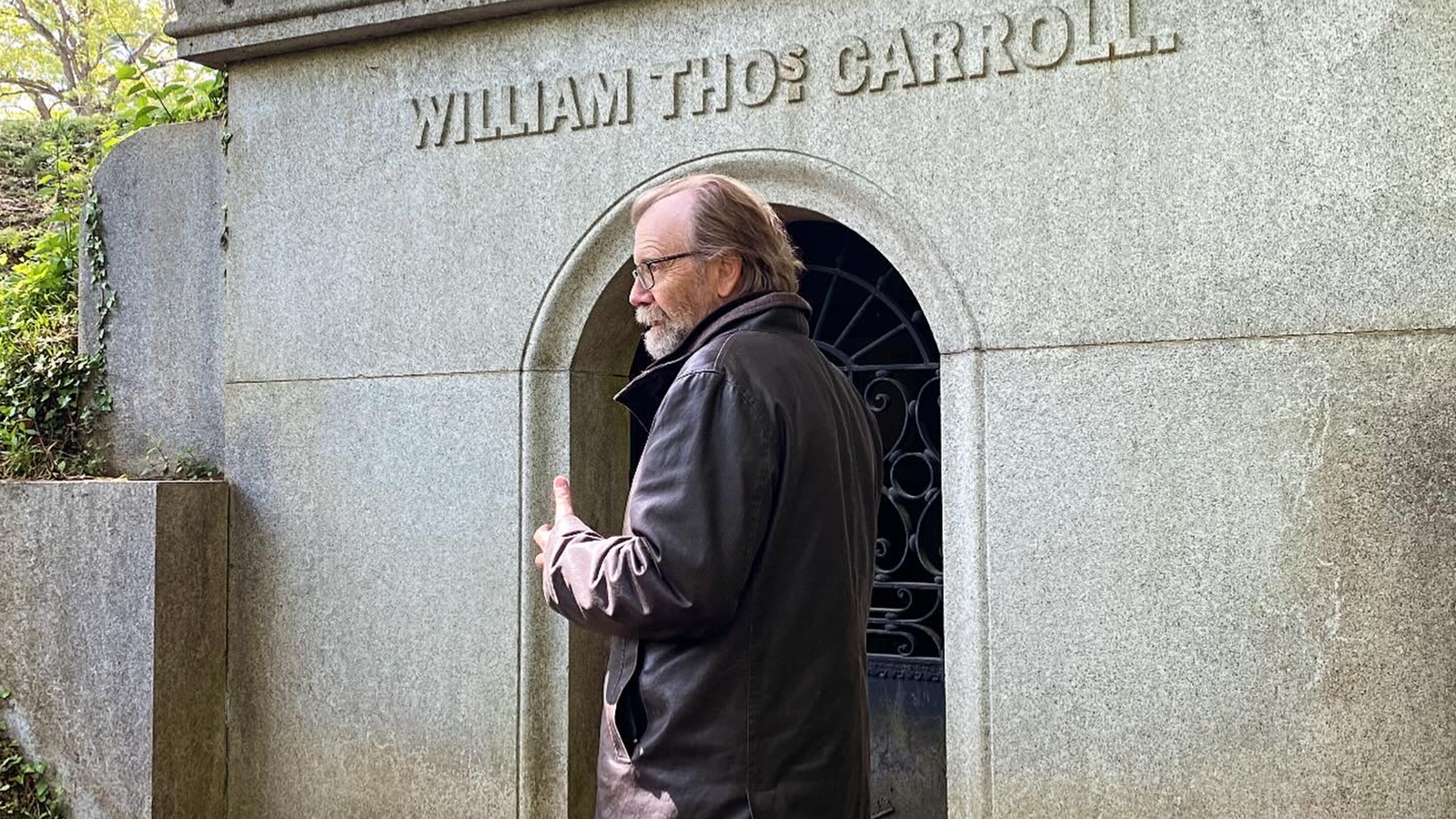

One day, not long after my first book – CivilWarLand In Bad Decline (1996) – came out, my wife and daughters and I were visiting Washington, DC. We were driving past Oak Hill Cemetery, in Georgetown, when my wife’s cousin gestured up at a crypt and said offhandedly that Abraham Lincoln’s son, Willie, had been interred in there for three years after his tragic death at 11 years old – and that, according to newspaper reports at the time, Lincoln had, on several occasions, entered the crypt to view, perhaps even hold, the body.

Well.

That got my attention. My mind filled with an image of the Pieta – the little boy draped across the grieving Lincoln’s lap.

I thought: “Wow, which could make a great book.”

But I didn’t feel that I was the one to write it. I’d made my reputation, such as it was, on ostensibly funny, vaguely futuristic short stories. And there didn’t seem to be much overlap between that skillset and what would be needed to write this Lincoln book.

So, I put that imaginary book aside and went on writing ostensibly funny, vaguely futuristic stories.

But… whenever I found myself in a place of artistic happiness, my mind would drift back to that Lincoln Pieta image and my heart would ache at the potential beauty of that book.

For about six years, on and off, between other projects, I tried writing it as a play – called Lincoln in the Bardo – but the result was stiff and formal, like a bad grade-school play. Finally, one New Year’s, looking back at what I’d done over the course of the previous year, I wrote, rather rudely, across the top of the play: RUN AWAY! DO NOT WRITE!

And that was that. Or so I thought.

In 2012, I published a story collection called Tenth Of December and that went pretty well, and I turned my mind to the question of what to try next.

I was getting older and didn’t want to be the guy whose headstone was going to read: “Avoided Doing What He Most Longed to Do.”

So, I gave myself a conditional, six-month contract. I wouldn’t tell anyone what I was doing. I’d just… goof around, with this Lincoln idea, for six months.

If it didn’t work, it could stay my little secret.

Writing that failed play had given me this much: Lincoln visits his son’s body in the graveyard and that event is narrated by a sort of Greek chorus of unhappy, trapped ghosts.

Now, as soon as we start a book, we run into problems. (That’s what a novel is, someone once said: a long work of prose that has something wrong with it.)

But problems aren’t really problems – they’re the way you find your book. Originality is really just acknowledging, and then solving, as well as you can, the problems that arise.

The first problem that arose for me was this: the story in my mind was very rich, informed by all of the history books I’d read over the years and what they’d told me about Lincoln’s complicated mental state at the time of Willie’s death.

For example, I knew that Willie had died at a low point in the Civil War, when Lincoln had been taking a lot of heat in the press, and just after the Lincolns threw this big party, about which the couple, I assumed, must have felt guilty.

How could I get this history into the book there? The ghosts, after all, wouldn’t know about it. (For a while I thought of using a really, really well-informed gravedigger, but that didn’t work.)

Finally, I asked myself: “OK, George, how do you know about the history?”

And ‘I’ answered myself: “Well, I read about it.”

Then I – well, you’ll have to imagine bifurcated me giving myself a sort of knowing look.

To which ‘I’ replied: “Wait, you’re saying I could just quote verbatim from those same history books I read?”

And the other ‘I’ replied: “Well, it’s your book, right? You can do whatever you want.”

So, I started quoting directly from the history texts. There was a certain skill involved in this: choosing the right quotes, cutting them down to size, arranging them in the liveliest order. I remember sitting on the floor of my writing shed, with dozens of historical quotes on cut-up pieces of paper all around me, arranging and re-arranging these until they seemed to make a certain sort of music.

Then, at one point, something needed saying more briskly than anyone had ever actually said it in any of those books, and I had the urge to just invent a text.

Again, I asked: “Can I do that?”

And again, I answered: “It’s your book.”

Lincoln was another problem. So much had been written about him that he’s sort of hardened into an entirely virtuous cartoon, which, in turn, makes him a potential musty snore-fest.

So, I tried to get him on- and off-stage as quickly as possible – not letting the reader take too long a look at him. I told myself that I was constructing a Lincoln, not representing the “real” one. “My” Lincoln was part grieving person (I’d been that); part loving father (ditto); part “man outside on a cold night” (ditto). The rest of him, I filled in with the best parts of myself – the most intelligent, generous, compassionate parts – and then I threw in a bit of my own self-blaming neurotic mind, because I sensed that he, too, might have had some of that.

And there he was, Lincoln, or at least a version of Lincoln; a cobbled-together simulacrum of a living man, sort of.

Soon, all of this problem-solving started making a world.

The ghosts were stuck in this place because they’d been unhappy in life, and/or because they didn’t know, or couldn’t accept, the fact of their own deaths.

As per Buddhist thought, our mind, while we’re alive, is like a powerful, wild horse on a tether. At the moment of death, the tether gets cut and the mind runs wild: our fears and habits get enlarged, we move around in space and time; things are exaggeratedly terrifying or exaggeratedly beautiful.

The ‘bardo’ of the book is sort of like the Catholic Purgatory except that, in “my” bardo, a spirit can earn its way out by accepting the fact of its own death and somehow coming to peace with whatever’s been tormenting them.

In the early parts of a book, the writer, like a juggler, throws some bowling pins up into the air. At the end of the book, he’s catching them.

I finished the book at our house in Oneonta, NY, one beautiful, frenzied autumn. I was up there alone and spending long, long days rushing back to the house on breaks to overdose on Graham crackers and crank Wilco and Sleater-Kinney and Copland’s A Lincoln Portrait to try to keep my energy and artistic standards up.

That fall, bowling pins were just raining down. It was as if the book knew exactly where it wanted to go, and I was just there to write it all down.

And I was in for big, lovely surprise there at the end.

All of these spirits have been in this bardo state for so many years, unhappy, self-obsessed, making themselves miserable and selfish with their efforts to ‘stay’. This has taken all their energy and gradually they’ve forgotten who they used to be; forgotten about joy and generosity and so on. But, toward the end of the book, I noticed, their concern for Willie started to transform them. Focusing on him, they started to come back to themselves; one person’s kindness would prompt a kind or helpful act from another person, in a process I started to think of as ‘viral goodness’, and that I recognized from life.

So: they save Willie, and he saves them. Willie, recognizing that he’s dead, leaves, and this, in turn, saves Lincoln, who goes back into the world and saves tens of thousands of enslaved people and, by doing that, saves his country.

None of this was planned. It just unfolded on its own, as I edited speeches that fall, and improved transitions, and tried to make things funnier and faster.

This is maybe the deepest lesson I took from writing the book: there’s part of the mind that is intense and wild; it’s more open, wiser than, than the everyday part. Art puts us in touch with this better part of the mind and reminds us that it exists, and that our capacity for understanding and forgiveness and ambiguity is greater than we might think.