What Audre Lorde Can Teach Us About Feminism, Love & Protecting Our Planet

Partway through Alexis Pauline Gumbs’ new Audre Lorde biography Survival Is A Promise: The Eternal Life Of Audre Lorde, Gumbs quotes from a poem Lorde wrote when she was just 14 years old: ‘I want to have the knowledge that when my life on Earth is done / that I have left something behind / for others to carry on.’

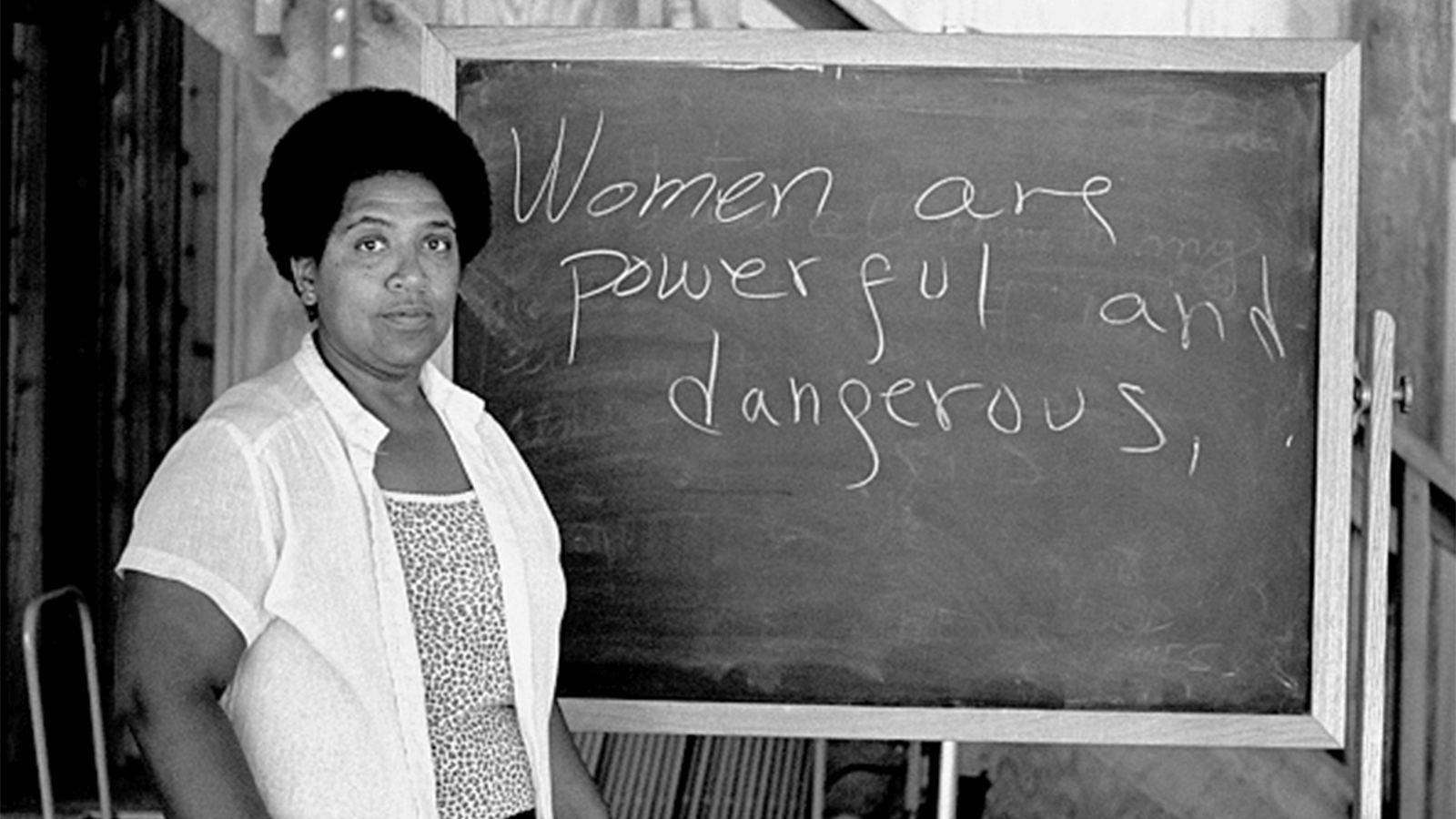

The popular activist and academic, who died (or as Gumbs writes, ‘began her afterlife’) from liver cancer in 1992 aged 58, has certainly left a lasting legacy. Today, it is common to see quotes from her numerous essays and poems across X and Reddit: ‘Your silence will not protect you’; ‘The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’; ‘Caring for myself is not self-indulgence. It is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.’

Offline, Gumbs reminds me, Audre’s words are often utilised rather more cynically. “[They appear] on the diversity centre wall or the grant proposal, or [in] the activist meeting that wants to give some lip service towards Black people or intersectional feminism, but not necessarily change anything,” she says.

Going beyond the – albeit powerful – sound bites, Gumbs’ biography excavates Audre’s life from birth to death, painting a rounded picture of the disabled child, hormonal teenager and forthright adult who became one of the most eminent Black feminist thinkers of the 20th century.

While there has already been a quasi-memoir (Zami, which Lorde described as a ‘biomythography’), a few biographies and two biographical films relesed about Lorde, Survival Is A Promise zooms in even closer than those that have come before. In part, because it covers ground not previously detailed in other biographies but also because Gumbs has written the book “like a collection of poems”, jumping back and forth in time across 10 sections and 58 chapters that pour over almost everything that came into Lorde’s orbit.

Gumbs – a poet, academic and activist who describes herself as a “Queer Black Troublemaker and Black Feminist Love Evangelist” – was keen to write a non-traditional account of Lorde’s life. “The form of the biography isn’t something I felt I was interested in,” she says. “But then, mentors of mine who’ve been Audre Lorde students – like Alexis De Veaux, who wrote the first biography of Lorde in 2004 – were all looking at me like, ‘Would you, please?’ So, I had to think about how I would relate to the form of biography. That’s why it’s a kind of a ‘queer biography’.”

Although she admits this book could only ever be “the smallest fraction” of what someone could say about Lorde’s life, Gumbs wanted to make sure it highlighted parts of her philosophy that rarely get mentioned, like the fact that “she was an environmental activist her whole life”.

Gumbs adds: “A lot of people don’t know that. And it’s not that they don’t know that because the information isn’t there. It’s just that it’s the most challenging demand her work makes of us – to be in relationship with Earth in a profound way. Clearly, we are in a space of complete crisis around our relationship as a species to this planet. So there was a clarity that came to me while I was in the process of doing this writing and listening to Audre Lorde. When I really listened to her… that was the piece that was like, ‘[the readers] need to know this’.”

Unusually for a biography, we hear from Gumbs throughout as she takes us through her research process, her thoughts and her reflections about the woman she has had an affinity for since she was 14 years old, first reading her work at a weekly writer’s workshop in ’90s Atlanta. Gumbs says of her first encounters with Lorde’s writing: “I felt like, ‘This is someone who is being transformed by love.’” She continues: “I started putting lines from her poems on the walls in my room. I started quoting her poetry for all my essays in high school. I wanted to be in that field that she activates in her work… The reminders of how complex and interconnected and beautiful and in a state of transformation everything is, is impossible to forget [when] engaging [with] her work.”

She was so inspired that she ultimately dedicated her college thesis to Lorde, spending hours in archives to better understand the person behind the writing. (This research shows through granular details provided in Survival is a Promise, such as when Gumbs refers to scribbles and crossings out in some of Audre Lorde’s notebooks.)

Gumbs even started a “night school” in her living room to teach people in her community about Audre. So it was perhaps only natural that one day she would be asked to write an authoritative book about her.

She started Survival Is A Promise during the height of Covid-19 pandemic, which meant she had plenty of time to go through the notes she had already gathered about Audre’s life. She tells me: “Maybe there’s a gift in being isolated; I had to think differently. I started thinking, ‘What did Audre Lorde read?’ You know, she read all this sci-fi when she was growing up. And I read so much about the poets that she loved, like Elinor Wylie, that weren’t really poets that I loved. And then, because she really studied Earth in a way that was profound – I had to follow her there, right? I had to learn and get into soil.”

Gumbs mentions the tendency to talk about Black feminist thinkers such as Audre, Fannie Lou Hamer and June Jordan as though they are only ever concerned with two things – race and gender. Many of us appear to have a “collective avoidance of reckoning with what had these folks mobilise” in the first place. But Gumbs is hopeful that those who read Survival Is A Promise will have a more rounded understanding of who Audre really was and what she believed. That at this moment – as the climate crisis gathers pace and war and conflict ravage marginalised communities – readers will “remember that Audre Lorde taught us that Earth is a relationship.”

Seun Matiluko is a British writer and researcher in law, race and politics. She has written for publications including Gal-dem, The Independent and Glamour, and is the host of the podcast Seun’s Talking Drum British And West African