Alana S Portero On “A Decade Of Reality & Desire”: Class, Queerness & The Promise Of La Movida In 1980s Spain

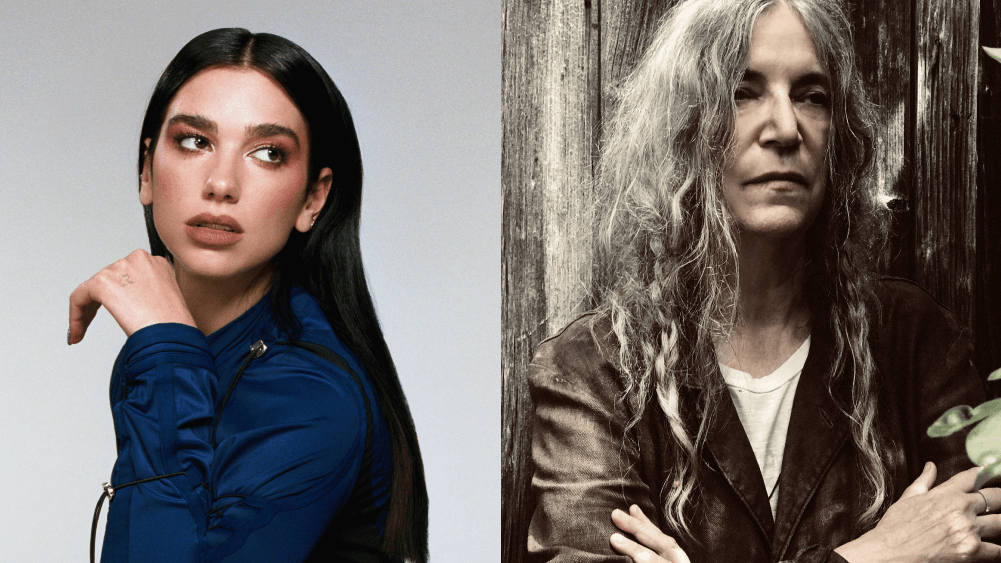

Alana S Portero is the author of Bad Habit – Dua’s Monthly Read for September – a coming-of-age novel set in 1980s Madrid, following a nameless Trans woman who confronts the realities of her identity during the La Movida counterculture movement. In this essay, Portero reflects on the intersection of class and queerness within post-Franco Spain, the history that is the inspiration behind her novel Bad Habit

The 1980s was the decade of reality and desire, where love met punishment, beauty danced with death. Heroin swept through Madrid, where I lived, like a biblical plague, and no bloodstain could prevent all that death from entering homes. “La Movida” (“The Madrid Movement”), a cultural, aesthetic and social, counterculture movement, exploded in Vigo, Valencia and Madrid: boys put on makeup and danced till dawn, while girls sang “Me gusta ser una zorra” (“I like being a slag”). And Pedro Almodóvar introduced us to the childhoods of gays, lesbians and five-foot transvestites, and that there was a pot of fun at end of the rainbow. In the Madrid of the ’80s, even with Francoism permeating the very walls of the city, the essential thing we drew from our gay childhoods was the possibility of fun, joy and being happy.

La Movida arrived to change that, but its reach was not infinite. All that hedonism occurred on two levels: the reality in the centre of Madrid, and the desire in the working-class neighbourhoods. We were the poor, strange girls who dreamed of the beauty that we saw on the big screen. We secretly danced to the songs of the pop goddesses. We wanted to be Boy George, Siouxsie Sioux, Tino Casal and Madonna. We dreamed of a handsome and tortured boyfriend, like Morrissey, or a cheeky and cool one like Dave Gahan, yet inhabiting that endless party of quasi mythological figures was forbidden to us.

La Movida, the New Romantics and synth-pop were a dream of hope that existed alongside fairies dancing in the night. These things were something to aspire to, something to project oneself into, but as working-class neighbourhood lesbians and Trans women, whether adults, teenagers or girls, we didn’t enjoy the privilege and prestige of Madrid like those wonderful creatures did. We could only immerse ourselves in its promise, which was a triumph in itself and something wonderful that kept us alive.

Class boundaries continued to affect gay lives as they always had. It was strange to live with the audacity of Almodóvar’s films and the baroque glam of Tino Casal, and yet at the same time see Trans and gay neighbours being mercilessly driven out of their homes, or being unable to find decent jobs because no one wanted them in the workplace.

When AIDS emerged, it was devastating to see some of the brightest stars of the time fall – those who had seemed invincible. It was as if they fell from the sky before reaching it. The mythology was decomposing before our eyes.

The political management of the AIDS crisis resulted not only in an enormous, universal neglect of people with the virus, but also served to fuel a violent stigma of sordidness and social danger. This reactivated the scenes of rejection and incomprehension that had been so arduously fought against.

I grew up with the absolute conviction that, one day, the virus would be transmitted to me and I would die young. The first people I slept with, my first lovers, carried Kaposi’s sarcoma like the imprint of a demon that had walked on their backs, faces and bellies. The discovery of pleasure and the body came hand in hand with an emptiness that can only be understood by those who faced it head-on. For my generation, learning about love and desire was a limited experience. We were initiated to the language of bodies lying on the edge: those who were going to die and those who would be saved. Our lives were like coins tossed into the air; they could fall heads up or they could fall down dead.

The gay scene in Madrid has always been extreme. Francoism, La Movida, the AIDS crisis, the conservative reaction following the stigma of the virus, the first decade of the 21st century of progress, popularity and urban paradise, the gentrification of the second decade, pinkwashing and instantly available news, a Conservative government that hates us and a population that embraces reactionary assumptions with ease, but finds it difficult to hate us because we are part of the DNA of this city. We are its night, its fun, its mischief, its pride, its value, its dignity, and the refuge whose doors are always open. Madrid is a city that likes to present itself as a conservative, aristocratic lady, but everyone, except herself, knows she is in fact a drag queen.

Watch Alana S Portero in conversation with Dua Lipa here

Bad Habit by Alana S Portero is out now