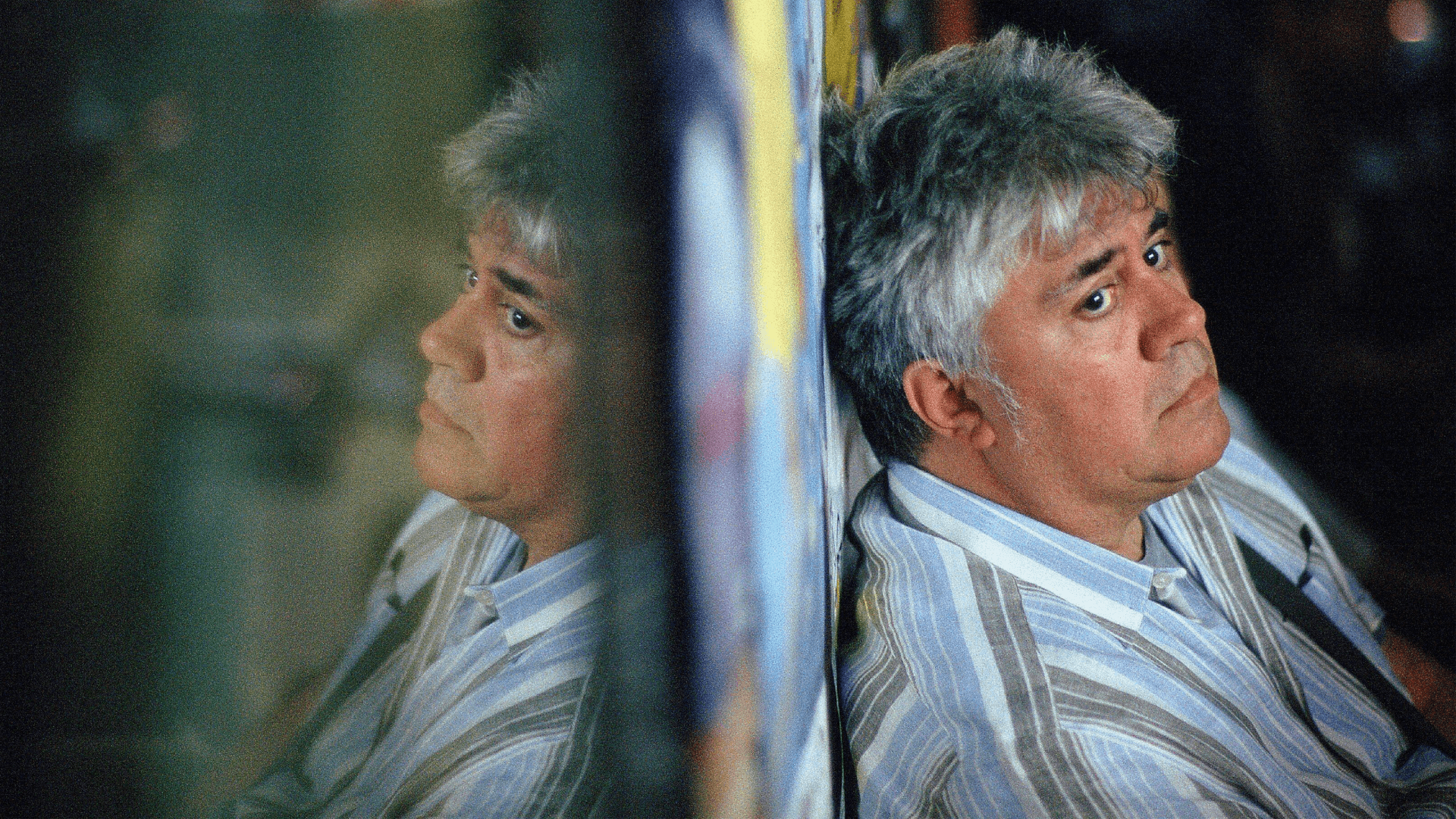

Pedro Almodóvar On His First Book: “I Feel Freer When I’m Writing Than I Do In Life”

Legendary film director and screenwriter Pedro Almodóvar is known for his captivating work onscreen. Now, he has turned his hand to a different kind of storytelling with the release of his first book, The Last Dream – a genre-crossing collection of short stories combining fiction with personal meditations. Here, he sits down with Alana S Portero – author of Service95 Book Club’s Monthly Read for September, Bad Habit – to discuss love, vulnerability and the power of art that draws on life…

Alana S Portero: Good afternoon, Pedro. How are you?

Pedro Almodóvar: I’m at a point where it’s best not to ask myself how I am. I’m caught in a whirlwind, talking about the film [The Room Next Door (2024)] as well as The Last Dream. I don’t believe anyone can truly predict how readers or viewers will respond. Promotion adds to the frenzy; there’s no time to reflect on how I feel, only the sense that I need to keep going. I should add that I’ve never given an interview without being completely honest. I think it’s the best way to do it.

Portero: The same thing happens in your work; you don’t know how to stop revealing details about your life.

Almodóvar: No. I feel freer, more uninhibited, when I’m writing than in my own life. I have absolute freedom, without any limits. I remember sometimes feeling concerned when the material alluded to me personally. In my life, I’m much more sensible and more reserved. You can’t always be candid.

Portero: There’s a quote by Tennessee Williams that came to mind as soon as I finished The Last Dream: “All good art is an indiscretion.” Do you agree?

Almodóvar: Absolutely. Listen, in some of the stories in The Last Dream that are autofiction, I feel like there’s a tell-tale version of myself inside me. And yes, art is an indiscretion, especially when it comes to your own life. Sometimes it even extends to your loved ones and those around you. I try to keep the ripple effects as small as possible though.

Portero: Do you agree that writing about others is an act of love that ends up leaving us alone?

Almodóvar: It’s because you’re writing in solitude. I don’t know how else to do it. The thing is, even when people are part of the narrative or you’re reflecting on yourself, fiction tends to seep in and elevate the writing. Take [2019 film] Pain And Glory, for example. While it’s often viewed as autofiction due to its clear resemblance to my life, there’s a lot of fiction woven in. People from my life appear in it, and I didn’t ask for their permission. I don’t know if I had the right to do this or not, but since I was being inspired by my own pain, I couldn’t avoid including those who had experienced those pains with me.

Portero: Capote, Williams, Cocteau, Slimani, Lorca, Cassavetes – there are references to all of them in The Last Dream. There are always many literary, artistic and cinematic references in everything you do. How did your early reading and cultural influences affect you? Talk to me about what awakened the creative spark in your life.

Almodóvar: I stumbled upon various works and authors – writers, actors and directors who blew me away. I loved the idea of escaping into another reality, far removed from my everyday life in La Mancha [the village he grew up in]. From the first time I saw images on the screen, I wanted to belong to that world, without knowing what that meant, or how to do it.

I watched everything, including swashbuckling films starring Jean Marais. I adored him. When I was a child, I saw a newspaper story about the death of Edith Piaf and Jean Cocteau, and it made a clear reference to the relationship between Cocteau and Marais. So I started looking for Jean Cocteau and discovered [1950 film] Orpheus and Amore – Una Voce Umana [Love – The Human Voice] [1948] by Rossellini, starring Anna Magnani. When I saw that film, I said to myself, “This is how I want to write. This is how stripped back I want my writing to be.”

Portero: In both The Visit and The Mirror Ceremony [stories from The Last Dream], religion is very much present, both in terms of its ritualism and iconography. You were educated in a religious boarding school. Tell me about your relationship with religion as a creator: Has religion been a literary tool for you?

Almodóvar: Yes. After my years at boarding school, I was completely enraged at the education I’d received. I was a child eager to learn, but the teachers I had were terrible. They made me feel illiterate, despite my deep desire to absorb knowledge. It was frustrating to have such enthusiasm stifled by inadequate guidance. What happens when I start to write is that I distort everything they taught me, as in Redemption – another of the stories in the book. It was a fun way of trying to get revenge and of finding my own style, using reality but always with a twist. I knew of at least 20 classmates who had been abused by priests. All of this left a poisonous and fertile seed in my mind that became The Visit and, 40 years later, Bad Education. My relationship with faith, which came about through abuse, made me an atheist at the age of 10.

Portero: In The Last Dream, Memory Of An Empty Day and A Bad Novel, there’s a vulnerability that I found not only moving, but extraordinarily literary. You open yourself up to frustration, loss, boredom and loneliness.

Almodóvar: All three are born from the actual moment in which they were written. One was the day after my mother’s death, a very painful event. Memory Of An Empty Day is also based on pain, in this case the pain of getting up one morning and being completely alone, not knowing what you are going to do that day, and not even knowing what you want to do. In A Bad Novel, I had just been in hospital. I’d had a delicate operation and after five days, it was the first time I’d felt a little better.

These were three moments of enormous vulnerability in which I threw myself into the void without any intention of creating a work. There is something in desperation, an energy that propels you forward without a safety net, and in those moments, I feel no shame. I find myself immersed in it. A significant part of my life unfolds in those states. I embrace them, accept them and work with them. Sometimes, it’s all you have.

The Last Dream by Pedro Almodóvar is out now (Harvill Secker, £16.99)