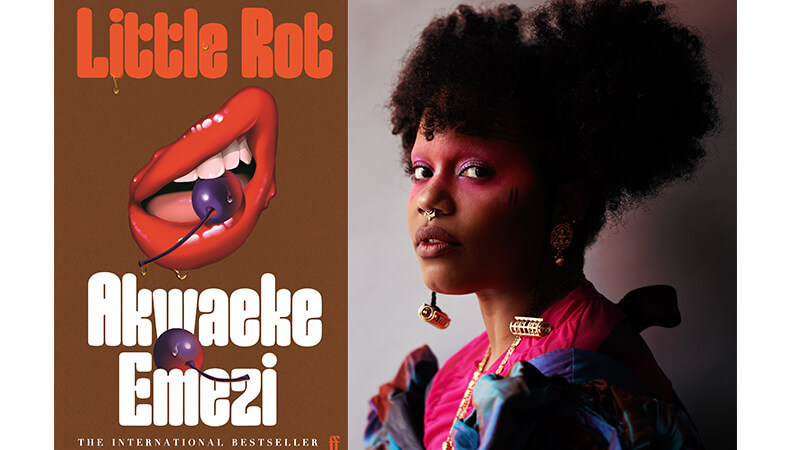

Read: An Extract From Akwaeke Emezi’s New Novel, Little Rot

Akwaeke Emezi is an award-winning writer and visual artist. Born and raised in Nigeria and now based in the US, they have achieved global acclaim for their books including Freshwater, You Made A Fool Of Death With Your Beauty, The Death Of Vivek Oji and Pet. Their latest novel, Little Rot, tells the story of five people over a single weekend in Lagos which will upend their lives. This extract is from the opening of the book…

The sun was setting in an oily splash of color, streaked blood in the sky under swollen clouds. A train circled the airport like a rusting tapeworm, lengths of loud metal dragging against old elevated tracks that the government could barely be bothered to maintain. Down on the ground, Aima looked up with nausea slicking greasily inside her. Metal screeched against metal as the train turned a corner, and she winced.

It had been years since she had stepped into one of those death traps; Kalu had insisted that a driver from his company shuttle her around since they had moved back home. She had thought she was blessed then, to have a boyfriend like him. He was generous, he adored her, and she was absolutely sure he’d never been unfaithful, which barely any other woman in the city could claim of their own partners.

None of that had mattered in the end. If there had ever once been anointing oil on Aima’s head, it had long since dried up, leaving her faith unhappy and flaking.

From the cracked sidewalk, she stared at Kalu as he pulled her suitcase from the boot of his car, his shoulders strange under his shirt, his face warped. His hair was cut low and neat as always. A plane whined above them as it descended, the sound fanning through the hot air. Kalu’s mouth was pressed into a stressed line. It looked out of place on his soft face—his mouth was always meant for easy smiles, his broad body for drowning embraces that Aima used to cherish. Her friends back in Texas had joked that Kalu was her personal teddy bear, somewhere safe and warm, someone who would never hurt her.

Now, he looked like a foreign place, and Aima wanted to tap him on the shoulder. He’d look up with those dark, dark eyes of his; and she would ask who he was exactly, what he was doing here, and what had happened to the man who had laughed with her in Houston and promised to never let her go. She didn’t move, though; she just kept staring as a dry breeze blew the tips of her black braids across her back. Aima had loved him for four, almost five, years, and this morning, after she’d booked her tickets away from him, Kalu had refused to let the driver take her to the airport. He’d slid behind the wheel himself, and for the whole ride, Aima had pressed her forehead to the glass of the passenger window, her earphones locked into her ears.

Over the gospel music she was playing, she’d heard ghosts—snippets of his voice trying to get to her, timid and weak attempts at connection, tendrils dying in the air between them. It was all small talk, nothing she could hold with both hands, meaningless chatter that avoided the truth of what they had both become. So, when they pulled up to the curb of the airport and Kalu had reached out to touch her arm, Aima had shrugged him off and stepped out of the car without saying anything. If he wasn’t going to talk about it, he didn’t deserve to touch her.

Her dress whipped loosely around her legs as she stood next to the car, and she could feel the eyes of the uniformed men at the door moving over her. She wondered if they could see her thighs through the flowered chiffon—it was thin, and her skin was bare underneath. “You should wear a slip,” her mother used to say. “Don’t be indecent. God is watching you.” But it was hot, and even though God had crawled His way into her life since she had come home, Aima didn’t think He particularly cared about her clothing choices. With a body as full as hers, she’d been hearing people call her indecent since she was a child. She smoothed her hands down the front of her dress and waited as Kalu placed her suitcase on the ground beside her.

The terminal for international departures was full of people seeing others off, families gathered with their children darting through a forest of legs, gorged bags being unloaded from taxis, voices flapping and thickening the air. Aima wanted Kalu to drive away, but she knew he wouldn’t leave until she was safely inside the building, as if someone was going to kidnap her from the pavement. As if another car was going to pull up, wheels smoking, arms and bodies leaping out to grab her and throw her inside and drive her off to a different kind of life, a secret part of the city, one that didn’t involve Kalu. But there was nothing, nothing except traffic and voices and polluted air and ruined love and a cracked faith. Aima sighed and watched dully as Kalu extended the handle of her suitcase, pulling it up in two sure clicks.

“You don’t have to go,” he said, and she stared at him.

Two and a half hours in traffic coming down from the highland because there had been an accident on the South‐South Bridge that squashed everyone into a single lane. There’d been blood on the road, a bus on its side, armed personnel guiding cars past. Two and a half hours, and it was now that Kalu had decided to find mouth. All that evasive small talk just to bring up the true thing when they were about to part.

Aima fixed her eyes on him and said nothing. His tone was an insult anyway. He’d made it too casual, as if he was presenting an informal option. He didn’t want to sound like he was begging her. Pride. Another thing she didn’t recognize in him. What other sins had he accumulated since they had come home? When had he become so set, so unwilling to be soft with her?