Life After Gal-Dem: What Liv Little Did Next

Why do we tell stories? Often, it is to understand our place in the world or to make others feel seen. It is why, in 2015, Liv Little founded gal-dem, the revolutionary publication for women and non-binary people of colour, which ran for eight incredible, re-defining years. Sadly, in March this year the publication announced its closure, leaving an indelible legacy on the world of publishing; and highlighting – long before whispers of performative activism – the need to platform hitherto marginalised voices.

Little, who said of the closure: “it might be the end of a chapter, but what a chapter to be a part of,” had walked away from the publication in 2020. It seemed a strange decision for a woman who had built an empire still at the top of its game. Yet Little, who Zooms me from the sofa of her home, her two cats intermittently clambering over her, tells me she had reached burnout point. “I’m someone who wants to take up space in many different ways, and my approach to storytelling has always been about not feeling fixed to one particular way of doing it,” she says. “Nothing lasts forever, and nothing must be [forever]. I would get really bored if I was doing the same thing indefinitely.”

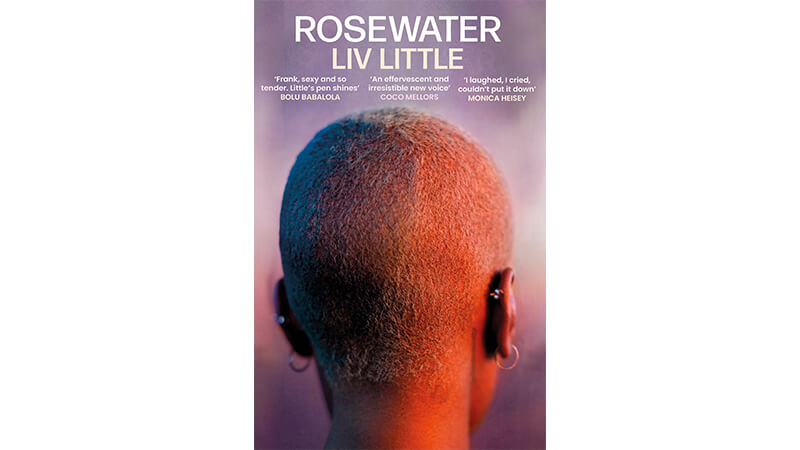

When Little left gal-dem, she enrolled on an MA course in Black British literature. At the time, she said: “You can only become a brilliant storyteller through the act of study.” The result of that course, and of her career pivot, is her debut novel, Rosewater. It’s the moving, powerfully executed tale of Elsie, a young, queer poet living in London, trying to find a sense of home – in every sense – after being evicted from her social housing. It has a lot to say about creating art in a capitalist society, about family and what homecoming can come to mean, if we fully embrace it.

“I wanted Elsie to be someone whose voice is important, which is why she is a poet,” Little explains. The poetry itself was supplied by real-life poet Kai-Isaiah Jamal, another example of Little’s inclination towards sharing space with other artists of colour. “The ability to connect with the heart through the mode of poetry and performance… that’s where Elsie’s magic and power lies, and that’s where Kai’s does too,” she says. “When they first sent me the [poem] on the Guyanese dish pepperpot, it reminded me of my mum, and really communicated what that food means culturally and spiritually. I cried when I read that poem.”

What draws Little to a story is character and finding that character’s voice. She describes Elsie as someone “uncompromising”. “I didn’t want her to be someone who was insecure about their Blackness, their queerness or their talent. She’s not any of those things. She knows that she’s good.”

After a personal tragedy caused Little to leave her MA course early, she describes a period of extreme sadness and disorientation. Perhaps, I suggest, the voice she was searching for was her own. “I think you’re right, maybe that was what I was trying to do,” she says. Rosewater would suggest she has achieved it.

Rosewater by Liv Little is out now

Marie-Claire Chappet is a London-based arts and culture journalist and contributing editor at Harper’s Bazaar